Sujata Chaudhri is the Founder, Owner and Managing Partner at Sujata Chaudhri IP Attorneys and specialises in IP litigation, enforcement, prosecution and transactions in the United States and India, particularly in the area of trade marks.

July 21, 2021

Q. Why did you choose to specialise in IPR?

I got into the IP field quite by accident when I was asked to assist a partner at the firm I worked at on an IP matter. Once I started working on the matter, the subject piqued my interest, and that interest just kept growing. I soon started reading up about trademarks, copyrights and designs during my weekends off from work. An LLM in IP followed and the journey with IP began!

The core motivating value boils down to first principles: be it a start-up or an MNC, protection of human intellect, in my view, holds utmost importance and deserves to be protected and cherished.

Q. During the COVID-19 pandemic situation, there are some essential innovations taking place across the world in the tech and medical spaces to provide much-needed relief to populations. Do you think trademarks and IPR can be a hindrance to more and more people getting access to such essential products?

The pandemic’s necessity has pushed the industry to make not only drugs and medical equipment like ventilators, but also essential technologies such as copyright-protected virus-tracing software.

Does the Indian patent regime strike a balance between this commercial interest and the interest of the ultimate beneficiary – the public at large? I think the 1970 Act is flexible and robust enough through its provisions on compulsory licenses, prevention of evergreening of patents and government acquisition of patents, to deal with public health emergencies as well as the objective of incentivizing inventors, if you see Sections 84-92, and 102.

But of course, unlike an epidemic, the pandemic is not a problem specific to one jurisdiction. A recent Oxfam report reveals that “a small group of rich countries representing 13% of the world’s population has bought up more than half of the future supply of leading COVID-19 vaccines”. This makes public access to Covid-relief a problem for densely populated developing countries, as you rightly pointed out.

But then, we already have a response from pharma companies such as AstraZeneca, in the form of sub-licence agreements with several producers, including the Serum Institute of India, to increase the supply of vaccines. AstraZeneca also is billing ‘non-profit’ prices for its vaccines for the duration of the pandemic. Gilead has licensed its Remdesivir patents to generic manufacturers in India, Pakistan and Egypt for supply in 127 countries. The World Health Organisation (WHO) established the Covid-19 Technology Access Pool (C-TAP) in June last year. The pool calls for voluntary contributions of patents and all other forms of intellectual property (eg, trade secrets, software and know how) from around the world in order to expand the development and production of new technologies needed in its response to the pandemic.

These responses, although voluntary in nature, are a concrete indication of the direction an incentivized, fairly dealt with, well-fed industry has the power to take- motivations likely bolstered by reputational advantages and pro-growth industry vision.

Looking at trademarks, there are enough safeguards in the Indian regime to safeguard the public from deceptive, descriptive marks such as a ‘COVID-RELIEF’, ‘NOCORONA’, ‘CORONA SAFE’ and ‘DHL CORONAVIRUS PREVENTIVE’, among others.

So even while the Registry is seeing abundant applications from shortsighted businesses filing to protect formative marks related to ‘Coronavirus’ and ‘COVID’, none of the applicants have started using the marks. Expectedly, there are applications which have been filed under Class 5 pertaining to medical pharmaceuticals, and veterinary products and even class 3 for cleansers styled on covid related marks, as well as class 9 for anti-virus software!

But the applicants – when they are active commercial ventures – could have perhaps used some IP due diligence before embarking on chasing such registrations.

Q. We are in the midst of an Artificial Intelligence boom. What are some of the challenges that AI is posing for the IP system?

There is the looming prospect that AI will be able to behave in human-like ways and IP will have to reevaluate the standard of “person skilled in art” which analyses any inventive step. Patent law, as it stands, attributes exclusive rights only to the true and first inventor, specifically to a natural person.

There’s also the problem of copyright ownership in AI. In order to be protected under copyright law, work must originate from an author’s own sufficient skills, labor, and judgment. This system poses a great challenge when trying to determine whether or not AI has used these factors sufficiently to produce such work.

Specifically on trademarks: The purchasing process is affected by information available to the consumer and who, or indeed what, makes the purchasing decision. AI has an impact on the information available to consumers and their purchasing decisions. AI is now used for several activities like “voice search”, this eliminates the usual text searching and there’s a projection that the visual aspects of a trademark may decline in importance with greater emphasis on phonetic and conceptual comparison.

Q. What are the major challenges that lawyers usually face in IP-related practice/litigation in India?

The challenges faced are many although these challenges are what makes practicing IP in India so interesting. Most stark among the challenges is the sometimes inconsistent approaches are taken by our courts and administrative bodies that are tasked with protecting valuable intellectual property. These inconsistencies are difficult to explain to clients who might have expected a matter to go well for them.

In terms of commercials, IP lawyers are now competing with the timelines generated by an AI driven world, in terms of commercializing business’ intangible assets. This brings up larger volumes of work to deal with on more competitive timelines, and a rather interesting challenge to manage.

Q. What sets the Intellectual Property practice at your firm apart from other law firms that also deal in patents, trademarks, copyrights, etc.?

The firm is set apart by the values of multi-disciplinary management, a youthful vibe, holistic decision making and a democratic culture.

I also feel that management practices come out better when they are developed with inputs from all concerned, rather than being imposed unilaterally.

Having the team participate in decision-making process makes it more democratic in nature and encourages greater acceptability. Moreover, it often brings to light diverse points of view, some of which may not have occurred to the management unilaterally.

Talent retention, in my view, can only materialize if the firm’s and team members’ individual goals align.

Before retaining talent, it is important to get raw talent, and then hone it in a way that works well both for the firm as well as for the individual. I’ve always believed that talent should be in-grown.

At my firm we have a well-laid down bi-annual evaluation process where each lawyer and paralegal is formally evaluated on their performance and growth in a transparent manner. The exercise helps in identifying the strengths and shortcomings in an individual’s performance, thereby paving the way for an individual’s growth as a professional.

We have incentives for efficient performers, and also a policy of fast-track progression in career for those who exceed the expectations of the firm. We’ve had fast track promotions in the firm, where lawyers are given responsibility right from early stages of their career, honing not just their technical skills, but also the soft skills such as delegation of work, mentorship, representing the firm at International conferences, practice development, building a brand, etc., which are vital from an entrepreneurial perspective. This has helped us hone and retain talent.

Q. On a personal level, how are you adapting to the changes in professional environments brought about by the pandemic and the lockdown? What do you like to do when you are not working?

We have tried to look at the uncertainty that came with Covid 19 as a challenge and an opportunity to reinvent the way we operated the firm. It has made us take a relook at every aspect and function of running the firm with a fresh perspective.

Using technology as our aid, we have allocated the time and resources saved that were earlier invested in travelling and physical interactions with clients in building the firm’s internal processes.

We have also taken a relook at our processes for hiring and recruitment. We saw a surge in practice in 2020, despite the pandemic, and consequently we scaled up our practice with new hires. There is a concerted effort to build up the firm’s patent department.

As for doing other things, most of my time away from work is taken up with my young daughter and our new puppy!

****

June 30, 2021

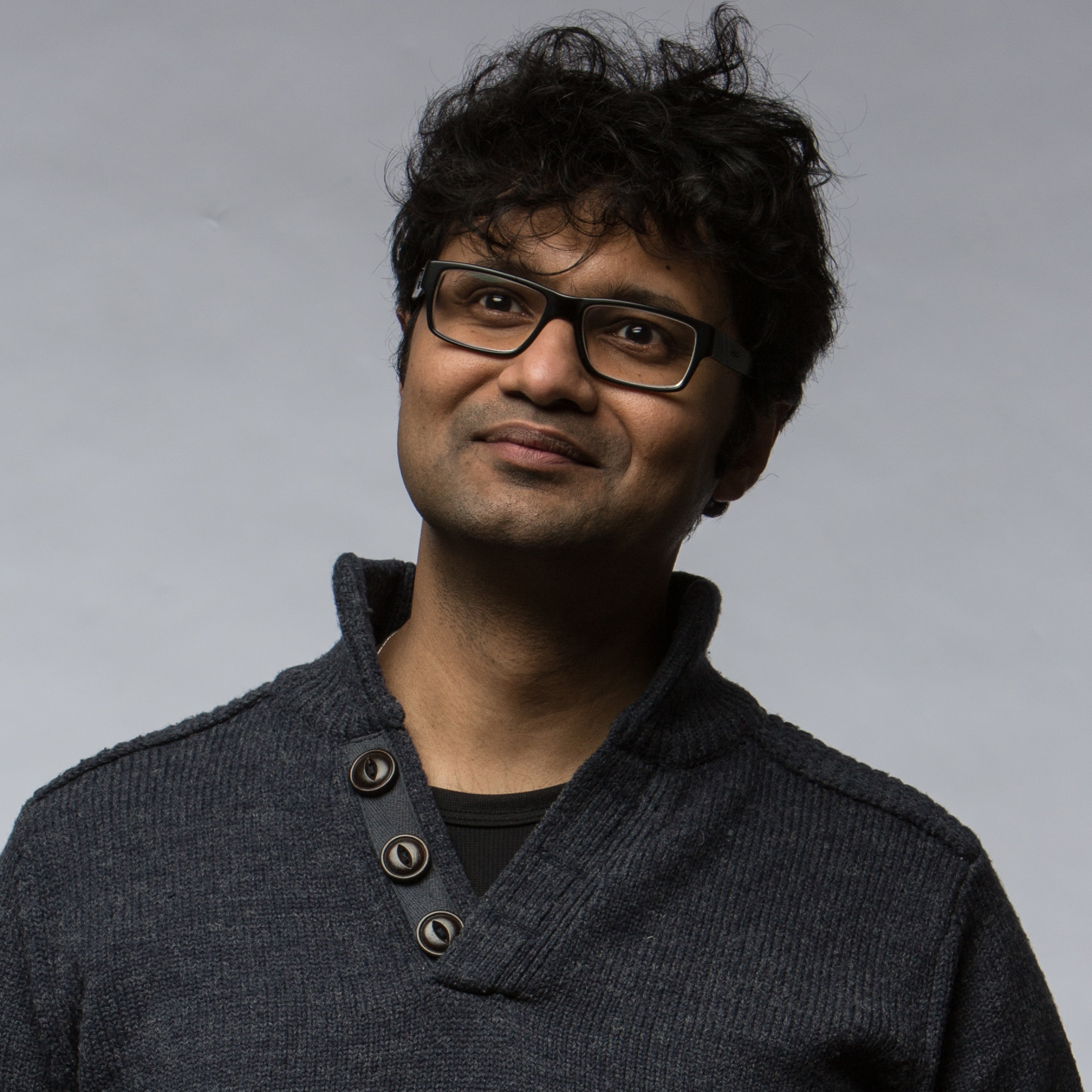

Abhir Datt is a lawyer practicing in Delhi, mainly in the areas of General Criminal Law, White Collar Crime, cases under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act and the Negotiable Instruments Act. He is associated with Atharva Law Chambers, a boutique law firm that has offices in New Delhi and Chandigarh.

Q. What are the qualities that a lawyer should have in order to practice criminal litigation?

In my opinion, anyone intending to have a career in criminal litigation must firstly hone the qualities of being meticulous and patient – the former for absorbing, understanding and mastering the facts of a case and researching the legal propositions involved, and the latter because sometimes results are delayed.

One never knows how any day in court will play out, and this is true across the litigation spectrum. While it is important to navigate through a case with a broad strategy in mind, it is equally important to be flexible and open to a change in direction, as the case evolves.

The contours of criminal litigation traverse many stages, with the trial being at its heart. The markers of an effective criminal trial lawyer are (a) a detailed mastery of the facts of the case, (b) a knowledge of the procedural and substantive legal aspects of the case, and (c) a grasp of this nebulous concept of “court craft”, which only comes with practice. It is needless, therefore, but important to say that one must be persistent, against all odds.

Regardless of which side you speak for, criminal lawyers inevitably work in close proximity with real life questions regarding constitutional rights to life, liberty, dignity, reputation and speech and expression. And so, it is crucial, perhaps above all else, to find something to ground us. Personally, I like to read. It helps to make better sense of the world I live and practice in.

Q. Do you follow any specific strategies when it comes to criminal defense? Maybe you could talk about the art of cross-examination in criminal cases.

The primary task I undertake with any brief is reading and re-reading it several times over in order to (a) master the facts, (b) identify the allegations against my Client, and (c) carve out the issues involved. The practice of this first fundamental task was inculcated in me by my senior, Mr. Manu Sharma, and it has shaped how I approach any case. Over the course of my experience, I have also learnt the importance of conducting independent investigations to understand the context in which the circumstances of any given case are set.

Finally, I cannot stress more here than I do with my junior colleagues, always start your legal research in the library, with the books. The time spent meditating over the brief eventually manifests in the strategy that is adopted at the stage of arguments on charge or cross-examination.

Strategy in criminal defence litigation largely depends on issues and circumstances identified during this process, which if left unchallenged may lead to unwarranted convictions, arrests or detentions. Although there may be different approaches to the manner in which a trial may be conducted, at the end of the day it is inevitable that as a defence lawyer one must bite away at the prosecution’s case, one circumstance or allegation at a time – there are no short cuts in this regard, fortunately.

Q. What are the major challenges that lawyers usually face in cases pertaining to White Collar Crime in India?

I think the major challenge is Perception and Prejudice, which has come to surround individuals accused of White-Collar Crimes. I often find that unsubstantiated and ludicrous figures are projected as having been cheated or laundered thereby making it seemingly a very “serious” offence or an offence of a “large magnitude”. This Perception makes it difficult for an accused to secure basic reliefs like bail or any other relief, at least until the chargesheet is filed and while investigation is undergoing, even in cases where otherwise the accused is likely to have secured such interim protections.

The other challenge, I find, is with respect to technical aspects of White-Collar Crimes, which sometimes require at least a first principle understanding of the nuances of accounting, core concepts of company law and economic policies.

Q. What has been the impact of COVID-19 on criminal procedure and law? Are there any key legislative changes? Do you believe these changes will impact how courts, investigating authorities, and enforcement authorities approach criminal trials?

It is difficult to respond to this question and avoid saying the word “unprecedented” for the umpteenth time since the COVID-19 pandemic arrived. That difficulty is insignificant in contrast to the frightening lack of accessibility that the pandemic brought with it. The Code of Criminal Procedure dates back to a time when neither today’s crisis nor conditions could have been imagined. Our Courts have tried to adapt quickly to a new mode of hearing cases.

Hearings conducted through the virtual mode have been effective in a metropolis like Delhi, and over time we have been able to establish a system for filing, mentioning, coordination, appearances, and arguments. However, a system is yet to be developed to carry out the recording of evidence, in a manner that ensures transparency and fair play, through the virtual mode. The major brunt of this lacuna has been faced by those undertrials who have been accused of serious offences, which matters are at the stage of recording of evidence, and have not seen any progress in their case. Similarly, investigation agencies also need to develop virtual modes of conducting interviews and investigations, in cases where the accused in unable to travel to the office(s) of the authorities.

The initiative of the Bench and the Bar in the decongestion of prisons by granting interim bail in light of the unique circumstance of the pandemic is one step that has been effective in retaining and recasting our constitutional ideals of fairness and due process. For the time to come, if we are to see the evolution of the e-filing and e-courts system to uniformly meet demands of access across the country, legislative intent will undoubtedly be key.

Q. In your opinion, is negligent spreading of COVID-19 a crime under Indian law? What are the laws that lay down obligations of citizens to prevent the spread of COVID-19? What are the repercussions in cases of non-conformity?

Where notionally in certain cases negligence may be made out, tortious jurisprudence has been minimal in Indian Courts. So, it is unlikely that we will actually see any such cases play out.

Q. Tell us about your law firm and what sets it apart from other firms.

We, at Atharva Law Partners, are a small multi-specialty boutique law firm that offer our retainer services, including in the areas of criminal defence litigation, civil/commercial litigation, matrimonial matters, property disputes, arbitrations and mediations, across a variety of fora such as the Supreme Court of India, the High Courts of Delhi, Allahabad and Punjab & Haryana, various tribunals and Trial Courts in Delhi NCR. We have a team of young and ambitious advocates who work together to provide our clients with a holistic approach to any case.

Q. Considering the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in the functioning of courts, in your opinion what kind of technological upgrade is required to ensure uninterrupted and efficient functioning of the courts and of lawyers’ practice in the country?

The digital transitioning of all our systems is inevitable, and the pandemic has hastened litigation into that process. Given that the shift to a digital interface does not appear reversible, it becomes imperative to invest in infrastructure that can support a virtual future for our judicial system.

Presently, there is some digital infrastructure in place which allows citizens to access public documents like orders or judgments passed by the Supreme Court of India, various High Courts across the country and some trial courts and tribunals. With respect to FIRs, in my experience, there is a scattered availability of these public records on government websites. As a primary step, these gaps in access to information need to be streamlined. For this purpose, it is crucial to establish dedicated IT departments in our Courts to (a) support the registry and the court staff, and (b) develop websites, software and applications to magnify the access to information about the cases that are pending in the judicial system. A similar department is crucial to support investigating agencies in adapting to digital tools, applications and software.

It would also be crucial to have investment going into (a) creating public spaces where virtual courts can be accessed and observed, (b) cloud storage for public records and documents and (c) development of applications that act as intermediaries between advocates and clerks, typists, translators, notaries and other support staff that work behind the scenes.

Q. Do you think Artificial Intelligence and legal technology in legal research can be helpful in improving the efficiency of the judicial system?

Absolutely. There is no doubt anymore that AI is the future of technology, as we know it. The market for IT products in the legal field is fairly young and rapidly expanding. In the past decade alone, there have been significant changes in the manner in which drafting, research and (now) hearings are being conducted. It goes without saying that these upgrades have helped make it easier to process copious amounts of information. I must admit, though, on a lighter note that I cannot help but fear the day that we see an AI algorithm designated as a senior!

Q. How has the pandemic affected you personally and professionally? How are you dealing with the changes brought about by lockdowns?

The pandemic has affected me both professionally and personally. Professionally, at the start of the pandemic, there was always an apprehension regarding how work would be conducted, whether the fact that we would not physically be present in office would impact work and if the judicial system was equipped to handle an online platform.

Professionally, we as a firm, have grown from strength to strength and adapted to the various challenges posed by the pandemic with dynamism and tenacity. Each and every person in the firm has stepped up to do their part to ensure that work runs smoothly. The fact that courts are now virtual has also been a blessing in disguise in some ways since it has moved everything online and the long commute to and fro the courts, which was previously a struggle, has been completely done away with.

On a personal front as well, the pandemic has been challenging. Being away from family and friends for long periods of time and being in constant fear for their well-being and safety has been difficult and has had a lasting psychological effect not just on me, but on everyone. I also got married in a small ceremony during the pandemic, which was a personal achievement for me, but definitely missed all my friends and loved ones who could not make it due to the situation.

That said, the Indian population is a resilient bunch and I have no doubt that we will all get through this together very soon. I am looking forward to interacting with each other in person on both a personal and professional level and am sure the future is bright!

****

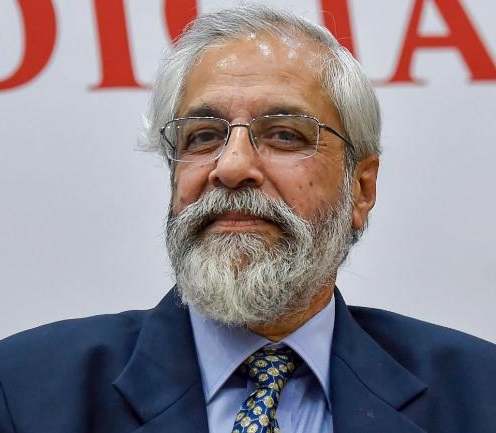

Mr Som Mandal is the Managing Partner of Fox Mandal, India’s oldest law firm that was established in 1896. He has been in practice for the last 27 years as a Constitutional and Corporate lawyer.

Q. What are the major challenges that lawyers usually face in cases pertaining to corporate and commercial litigation in India?

The challenges faced by lawyers in this regard are manifold. Corporate and commercial disputes pose many vexed questions of facts and law which require availability of a good pool of experts which is not easily available in India. A good expert having specialized domain knowledge is of great importance to establish a foolproof claim or defend one.

Secondly, quick and time bound resolution of such cases has always been a problem. The Commercial Courts established recently which was expected to give time bound resolution of commercial disputes has not yielded the desired results. The dispute resolution even under Alternate Dispute Resolution (ADR) mechanisms such as mediation and arbitrations have given mixed results. Though Courts are increasingly referring disputes to mediation to give it an impetus, however, it is yet to gain adequate currency. As regards arbitrations, the arbitration process itself has become time-bound, however, the time taken to execute an award or a decision in a challenge to the award, which is through the Courts, remains time consuming.

Q. Could you talk about some of the most interesting cases that you have worked on and which proved to be either great learning experiences or turning points in your career?

It is difficult to recount done in this short space the interesting cases that one has worked on. However, the one interesting case that always comes first to my mind is a commercial litigation matter that I did many years ago which was very significant in its impact and particularly memorable because of the swiftness with which we had to act and approach the Court. I was representing Barbara Taylor Bradford (Author) in a litigation against a T.V. channel with respect to a daily soap that was going to go on air that day. Our contention was that the soap was a total lift from my client’s book and the makers of the soap had not even bothered to give credit to my client leave alone any monetary benefits. We filed for an order of injunction asking the Calcutta High Court for an order of stay of the telecast that evening. The Calcutta High Court refused to give stay. We got the order at around 12 pm and by 4 pm that same day we were ready with a Special Leave Petition to be filed in the Supreme Court against that order. We ran to the Supreme Court with the SLP, petitioned the Registrar for a hearing before the Court that very evening because the telecast was to start late night, managed to get the SLP listed for that very night, appeared before the two Hon’ble judges who kindly agreed to hear the matter at their residence and managed to obtain a stay on the telecast. We got a copy of the order and hurried to the office of the TV channel to serve it upon them because if the telecast was to be stopped the TV channel had to be served with the Supreme Court’s order. Needless to say, the TV channel was hostile and unwelcoming — the notice had to be pasted at their various offices. The end result however was very sweet. We saved the day for our client and the telecast was stopped. We managed to achieve all this in a matter of 5-6 hours-right from the drafting of the SLP to managing to serve the Supreme Court’s order on TV channel. The thrill of those few hours is hard to forget.

Q. The Arbitration scenario in India faces criticism for not being upto the mark especially in comparison to some other countries. What do you have to say about the mechanism for institutional arbitration in India and its comparisons to countries like Singapore, London, etc.?

In India, arbitrations were synonymous with ad-hoc arbitrations. However, the Government has of late taken several steps to institutionalize arbitrations in India. In December 2016, Government of India constituted a Committee under the Chairmanship of Justice B.N. Srikrishna (Retd.) with the view to review and reform the institutionalization of arbitration in India. The Committee gave its report and a new bill was introduced i.e. the New Delhi International Arbitration Centre Bill. This Bill was passed by both the Houses of Parliament and enacted as “The New Delhi International Arbitration Centre Act, 2019”. This Act provides for establishment and incorporation of the New Delhi International Arbitration Centre for the purpose of creating an independent and autonomous regime for institutionalized arbitration in India. We already have the Mumbai Centre for International Arbitration which is doing good work as an institution regulating arbitrations in India.

Hopefully in a couple of years, India’s arbitration institutions will be a force to reckon with and will be comparable to the LCIA, SIAC or the HKIAC because we have a lot of homegrown talent practicing arbitration in India and India as a destination for arbitration will be much more cost efficient than London or Singapore which are expensive cities.

Q. In your opinion, what is the scope of Alternate Dispute Resolution in India?

The Indian legal system has been known to be expensive and time consuming. These are the reasons why corporate houses and multinational entities are hesitant to submit themselves to the jurisdiction of Indian courts. With the rise of economic liberalism in India, these drawbacks became very apparent and led to the rise of Alternate Dispute Resolution in India. Arbitration became increasingly popular as large corporate multinationals wanted to choose their arbitrators themselves and submit themselves to the jurisdiction of their choice.

Gradually arbitration percolated to domestic entities too and now arbitration (mediation and conciliation have still to catch up) is the preferred mode of dispute resolution in commercial contracts. Almost all types of disputes can now be referred to and adjudicated by arbitration.

With the recent amendments to the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 in 2015, 2019 and 2020, the process of arbitration is to proceed in a time bound manner. The fees of arbitrators have been regulated. So, an effort has been made to make arbitrations less expensive and time consuming. The Government is also making efforts to make arbitrations as litigant friendly as possible. All these measures will go a long way in making arbitrations and other modes of ADR more popular means of dispute resolution and increasing their scope and prominence.

Q. Do you think Artificial Intelligence and legal technology can be helpful in improving the efficiency of the judicial system?

AI and other technology can be of immense help to the judicial system and to a great extent can help unburden the Indian Courts. There are experiments going on in other jurisdictions where aid of legal robots is being taken to write judicial orders. Advent of AI in legal research can immensely help the judges in writing their orders in India too. Similarly, even the lawyers can help litigants with efficient use of AI to cut down legal costs. Use of technology can also help in the efficient management of the procedural aspects of the functioning of the judicial system such as case listing, apportionment of Court’s time for each case, Court’s interface with the litigants and lawyers etc.

Q. The coronavirus pandemic has changed the way not only lawyers and judges work but the way the entire legal system functions. How have you adapted to the lifestyle changes, both personally and professionally, that have been brought about by the pandemic?

Work from home has become the new normal in this pandemic. We have been constrained to shut our offices in lockdowns so all our work is mostly done from home unless of course, there is a deadline where it becomes imperative for the team to meet in office physically. I am no exception to this trend and have adapted to this well. My days are packed with virtual calls and meetings and I am slowly getting used to reading longish documents also on my laptop which was not really something I was used to before the pandemic. It is a strain and yes, I do crave for my dog-eared and highlighted paper files but there is no option. The pandemic has thrust technology upon us in a rush and we are all grappling to be one up on it. However, I am so looking forward to a time when I will be able to meet my team and clients physically every day and greet each other with that warm handshake.

***

Debanshu Khettry is a Principal Associate of the law firm Leslie & Khettry.

Q. There is a common perception that first generation lawyers have to struggle more than those who come from a family of legal professionals. Could you give us a glimpse into the other side of the story. Being a fourth generation lawyer, have you faced challenges in your legal career? Do you think there is always a benchmark against which your performance is evaluated?

It is probable that first generation lawyers struggle more than those who come from a family of legal professionals. However, coming from a family of lawyers has its own inhibitions. You are always compared to your forefathers or seniors in the family. The base or the standard with which you start is already raised. If you are evaluated against a set benchmark, the stakes are higher because you not only have to aspire to rise to the expectations but also ensure that you protect the reputation generated by your forefathers. Compare this to a person who is starting afresh, has very little to lose. The next generation has to ensure that not only do they protect the downside (what the previous generation achieved) but grow further. I feel that it is always more difficult for the next generation.

In addition, each generation has to prove himself / herself since the laws are ever changing and so is the work pattern along with outlook and requirement of businesses / clients.

Q. You graduated from NUJS, Kolkata and thereafter you pursued your LLM from UCL. How different is the legal education system in the UK as compared to India?

It may not be fair to do a comparison as I did my undergraduate from India and postgraduate from UK. The teaching methodologies may differ with the nature of the degree / programme being taught. Having said that, I noticed that in India there is a great deal of focus on lecture method whilst in UK the emphasis is more on the Socratic method.

Q. Being the co-founder of P-PIL, with a vision to promote practical advocacy among law students, do you feel that there is a lack of practical training in law schools in India? How can this gap between learning law and its practice be bridged?

There is definitely a gap between learning law and its practice in law schools in India. To some extent the gap is bridged by focus on internships and platforms such as P-PIL. There are many practical courses these days (within or outside the university) which students can consider taking based on their interest areas. Law schools should also encourage inclusion of practical modules apart from theory-based modules in their course structure.

Q. You are the founding member of IDIA and founding executive editor of Journal of Telecommunication and Broadcasting Law. You are also the co-founder of P-PIL, SILC and Lawctopus. What has been the decision factors behind the creation of these ventures?

Each of these ventures is the result of efforts of several others and a gap in the industry that needed to be filled. The Increasing Diversity by Increasing Access (IDIA) project was the brainchild of Late Prof. Dr. Shamnad Basheer. The emphasis is to promote diversity in law schools by uplifting the under-privileged. The Journal of Telecommunication and Broadcasting Law (JTBL) was the result of lack of any journals devoted to the ever-growing, vital and complex field of telecommunication and broadcasting laws.

Similarly, for Promoting Public Interest Lawyering (P-PIL), we wanted to create a platform from where students can get an experience of practical advocacy which unfortunately is not fully achieved with the current system of mooting in law schools. The Standard Indian Legal Citation (SILC) was also conceptualised due to the absence of any indigenous citation methodology designed to cater to the reference of Indian legal sources.

When we started Lawctopus, there was no website that offered information on the various opportunities available to students or an insight into how their internship experiences at various places have been. The portal helps law students and aspirants make informed choices.

One of the major inspirations behind these ventures was Mahatma Gandhi’s oft-quoted phrase ‘Be the change you want to see in the world’. It is easy to remark that there is a problem or there is a lack of a better solution, nevertheless, each problem or the lack of a better solution is an opportunity that can be seized.

Q. You are part of your family’s legacy firm, Leslie & Khettry, which was established in the year 1944. Could you share with us the history behind this extraordinary journey of 76 years?

If one sees our Firm, Leslie & Khettry’s logo, there are 3 rising stars followed by the words practising since 1944. This was carefully thought out because we want to indicate that there is something before 1944. The Firm was started by my grandfather (Sreenath Khettry) in 1944, however my great grandfather (Golap Khettry) was also a lawyer at Calcutta.

Q. Technology has revolutionised the way the law firms and how lawyers work. How do you see the development of technology in the future affecting your work?

Technology is both a boon and a bane for lawyers. On one hand, it brings in efficiencies and creates new opportunities. For instance, the adaptation of e-courts will help lawyers who have multiple hearings in a day and it also opens the door for making appearances in courts at different cities or locations. However, technology is making a lot of legal skill sets redundant. For instance, you can get due diligence done by bots instead of lawyers. We may also have bots who will predict the outcome of a case on the basis of precedents and various other inputs.

Q. What are your future plans professionally? Do you plan to expand Leslie & Khettry?

Yes, we are already expanding organically and will not shy from looking at inorganic growth opportunities. Our plan is to grow our practice and cater to the needs of those requiring legal assistance to the best of our ability. We do not call ourselves experts of anything and we are always students / practitioners as law changes its shape on a daily basis.

Q. What are your other interests, other than law?

I have deep interest in finance and how the financial markets across the globe function / react to various events. I also devote some amount of time in doing angel investments and meeting entrepreneurs and understanding their needs. I also enjoy engaging in new activities, be it learning a new language or an instrument or taking up a sport.

****

An Interview with Prof (Dr) Amit Jain, Pro- Vice Chancellor of Amity University, Rajasthan and Prof (Dr) Saroj Bohra, Director, Amity Law School, Jaipur. The Amity Law School, Jaipur was recently enlisted among the Top Laws Schools in India in the Legal Powerlist 2020 organised by Forbes India and Legitquest.

May 20, 2021

By LE Staff

Q. How does the teaching methodology practiced by your institute instill knowledge, skills and analytical thinking in students to prepare them for the challenges they may face as young professionals in the legal field?

Prof (Dr) Saroj Bohra: Law has always been taught with the help of theories, principles, their practices, and applications. Law, as it is invariably known, consists of multifarious areas each linked with the other. The task relevant for teaching these subjects is to bridge the gap existing between them. At Amity Law School, Jaipur, we follow a perfect blend of the lecture method, Socratic method, role-play, case studies and simulations, group discussions, tutorials, projects, seminar method, cafeteria model (teachers and students residing in campus holding discussions over a cup of tea or coffee is popular wherein everyone expresses their opinions freely), visits to courts, jails etc., special guest lectures, and technology-enabled blended learning using digital resources.

Prof (Dr) Amit Jain: We, at AUR, provide a supportive environment that facilitates creativity and innovation. Our well-structured and flexible curriculum allows students to master skills to face diverse challenges of the corporate world. To make our students industry ready, workshops, seminars and guest lectures are delivered by industry experts. The strong foundation provided to our students offers them an edge not only to face competition but also generate employment opportunities. Our state-of-the-art infrastructure and facilities complement our academic ecosystem and enhance teaching-learning processes. We encourage our students to discover new perspectives, see things differently and develop an entrepreneurial mindset. The faculty members interact constructively with each other and provide great learning opportunities for students. The students of AUR develop team building, leadership, communication, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills, all of which are suitable for a variety of fields of employment.

Q. Do you think the use of technology can support and enhance the education of your students? What kind of technology has your law school put to use for the benefit of students?

Prof (Dr) Amit Jain: Technology has proved to be a great enabler during the unprecedented time that we have faced due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The university has in-house intranet system ‘Amizone’ which provides a platform for easy connection between teachers and students and provides ready information about course-profiles, class schedule, and assessment plan.

In addition to Amizone, the university has also subscribed to secure and multi-function online delivery platforms for all its academic and administrative operations including regular teaching-learning and continuous assessment activities. This added to the smooth conduct of teaching-learning activities during the COVID 19 Pandemic.

Recorded video lectures, e-books, continuous assessments through digital tools, interaction with industry experts through webinars, online career guidance sessions, and mentor-mentee meetings ensured that the quality of academic delivery and routine activities are not compromised at all during the nationwide lockdown.

The faculties completed all academic activities through the virtual mode. All the assessments including end semester exams were also conducted online through pre-existing Intranet facility of the University.

Prof (Dr) Saroj Bohra: Today, knowledge recall systems are being automated by tools easily accessible on the market. Given the level of automation we are experiencing, efficiency dictates that repetitive routine tasks are going to go; analytical skills, strategy, ability to problem-solve are coming to the forefront and of course ability to interact with technology is becoming critical. Therefore, there are definitely changes to legal services and how students will deliver these services.

Answering the second part of question, Amity Law School (ALS), Jaipur is one of the first law schools in introducing legal technology training programmes. Its working pattern is as well automated through the use of Amizone (Amity Intranet Zone), which is the campus management system covering all academic administration related processes from admissions to alumni which can be accessed by keying in URL address https://amizone.net, operational since 2009. The course plans, assignments, lesson plans, study material, attendance, results all can be uploaded and downloaded by teachers and students.

During the lockdown, the IT department had organised workshops on online teaching platforms, which helped to swiftly switch academics from traditional classroom to online teaching-learning and assessments. On MS Teams platform teachers and students are connected with their institutional email id by IT department and online classes are conducted. Teachers can record their lectures which could be referred to by students in future. So, we have two effective platforms to connect online with our students Amizone & MS Teams where teachers could also conduct their class test, project or article or mooting presentations and take assignment submissions. Course plans are exhaustively prepared including the session plans and continuous assessment components. The continuous assessments are carried out across the semester and the components are planned based on learning objectives and learning outcomes of the course. Academic calendar is also shared with students on the commencement of the session. Everything is uploaded online for students’ ready reference and implementation.

Amity’s Jaipur campus established Amity Innovation Incubator and E- Cell to encourage and promote entrepreneurship skills among the students. We have partnered with the industry for better stakeholders connect for this we have established Industry Advisory Board too. We are excited and hope that learning opportunities of the future will reinforce, complement and to bring to life new and holistic experience for our students.

Q. Prof Jain, you often interact with faculties at educational institutes abroad. You have also been visiting faculty at universities in Australia and Europe. Do you think there is a difference between the way academics (specifically in the legal domain) function in India and in other countries? Where do you think India lacks or needs improvement as far as legal education is concerned?

Prof (Dr) Amit Jain: I believe we live in a globalized world and modern teaching methods are the same globally. However, in the western world it is observed that education is more practice oriented, and focus is more on skill development rather than knowledge dissemination. Indian legal education providers are also not behind their global counterparts. At Amity University Rajasthan we organize many competitions like Model United Nations, Moot Court Competition, Trial Advocacy Competition to provide a simulated environment to our students that helps them to practice and hone their skills. Internships play a vital role and industry academia collaboration is required to strengthen the curriculum in line with industry requirement. At AUR we have a very strong Industry Advisory Board that meets regularly to suggest improvements in our curriculum as well as pedagogy. Legal Education in India should provide opportunities to the students to work on real life problems with the support of industry mentors.

Q. The coronavirus pandemic has changed the way we live and work, and the change has probably hit educational institutions the most. What has been the impact of the pandemic-induced lockdowns on your institution?

Prof (Dr) Saroj Bohra: Well, due to the lockdown and even post-lockdown as precautionary measures education institutions are closed. It was an unprecedented situation and I consider the facilities of internet and technology as a blessing in disguise because of which we are connected with each other and engage ourselves productively in these trying times. Amity University Rajasthan has overcome all the difficulties by quickly adapting to the virtual online mode of teaching not only for the students of law school but also for the students of Amity organization as a whole in India and as well outside India.

In March 2020, immediately on lockdown ALS adapted to the online teaching. Besides regular, remedial classes were also conducted. Groups with students, teachers and staff on social platforms created so that all are connected all the time. Even End Term examinations for final year students were conducted online on Amizone platform. Thereafter, ALS took up the initiative of organizing webinars hosting successfully over a dozens of webinar inviting experts from the various domains of law and as well from legal firms

Students have been provided with remote access to online data resources. Corporate Resource Centre assisted the students in appearing for online interviews and students were placed in reputed national international companies like FHS, Nishith Desai Associates, Khaitan & Co., Amicus legal, and Innodata to name few.

Online Board of Studies meeting, Ph.D. viva of three research scholars of ALS, Student Research Advisory Committee presentations, Student Research Degree Committee meeting, departmental meeting, HOI’s meetings, Academic Council meeting, Online Farewell of final year students, Online Orientation of Freshers, online weekly Mentor- Mentee meetings etc. were conducted.

Overall ALS had given its best in making this COVID-19 time successful for its students and engaged them in online learning and initiated a sense of innovation to come up with new ideas. Modestly, pandemic has not changed the functionality of Amity Law School. Only the mode has changed from physical to virtual, rest all is same. Now even our new academic session is in full swing.

Prof (Dr) Amit Jain: The pandemic situation no doubt created challenges for almost every sector including education but at the same time as said, “in every adversity lies an opportunity”. Institutions were quick to respond and moved to online teaching and learning. Amity University Rajasthan was among the pioneers in country to implement an Online learning system to ensure continuous learning. Prompt action from faculty and staff helped students save precious time and kept them engaged in productive work. Removing the barrier of geographical boundaries and location an Online Learning system also helped to develop a sense of responsibility and discipline amongst students. No doubt, faculty and student missed the 152-acre state of the art lush green, eco-friendly campus of AUR but technology brought us closure to global resources and experts. We could organize webinars and expert lectures from global experts with the help of online platforms. Student also could connect at different occasions with 1,75,000 Amity students globally.

Q. How have you personally adapted to the lifestyle changes that have been brought about by the pandemic?

Prof (Dr) Saroj Bohra: To say that the novel coronavirus pandemic has changed the world would be an understatement. In less than a year since the virus emerged, it has upended day to day lives across the globe. The pandemic has changed how we work, learn and interact as social distancing guidelines have led to a more virtual existence, both personally and professionally. Now most of the time is spent before screen so I have tried to maintained regular routines as much as possible and retained a daily schedule for self-including sleeping, meals and activities. I have stayed socially connected by talking to near and dear ones using the telephone, video calls or messaging. Staying in university campus is an advantage as I could take regular walk and exercise, of course, following the govt. guidelines. Also now I could spend some quality time with my son. My role as an academician, administrator, mother keeps me almost entire day occupied, however, now find some time for my hobbies and to do my research work.

Prof (Dr) Amit Jain: Though It was a nationwide lockdown due to the pandemic, it was also an opportunity to read, reflect, revive, and rejuvenate oneself. The faculty and staff members including myself were not behind in terms of keeping themselves updated and self-develop. We undertook online courses and certifications available at online platforms. It was a time to build skills and sharpen the saw. The situation was full of chaos and confusion, but routines for faculty and students were made very structured beginning with online yoga session, pranayama, and meditation sessions during morning hours followed by regular classes in the afternoon and industry webinars during evening hours. In difficult times like this it is important to keep our immunity intact and keep oneself emotionally and physically fit. I ensured constant touch and communication with the team through online meetings to ensure that they stay motivated and do not get perturbed by environmental changes. I personally wrote appreciation letters to team members for their dedication and contribution during the pandemic.

****

Prof. (Dr.) Amit Jain is Currently Pro-Vice Chancellor at Amity University Rajasthan. He holds a Ph.D from Sardar Patel University and has completed FDP from IIM Ahmedabad.

Prof (Dr) Saroj Bohra is Director, Amity Law School, Jaipur. Her qualifications include B.A.,LL.B (Gold Medalist), LL.M., Ph.D.

Satyam Thareja is a post-graduate of Indian Law Institute, New Delhi (2015) & graduate of National Law University, Jodhpur (2012), practicing as an independent legal professional in Delhi. He is also an Advocate-on-Record at the Supreme Court of India.

Q. What are the practice areas that you specialise in? Could you talk about some interesting cases that you have worked on?

Immediately after graduation in 2012, I got to work as a Law Clerk-cum-Research Assistant at the Supreme Court of India in the office of Retd. Justice R. M. Lodha, who later became the Chief Justice of India. Thereafter, I got an opportunity to work as an associate in the Chamber of Mr. Sidharth Luthra, Senior Advocate & Former Additional Solicitor General of India. Since 2016, I have been working independently on matters pertaining to criminal law with focus on criminal trials. Apart from that, I have been rendering assistance to my father Mr. GP Thareja who retired as a Judge and now actively practices in Delhi. My experience with him gave me additional exposure to criminal law, apart from exposure to nuances of the Delhi Rent Control Act and the Code of Civil Procedure.

During this time, I also got an opportunity to assist the Hon’ble High Court of Delhi in matters titled Satya Prakash v. State (Crl. Rev. Pet. No. 338/2009) & Rajesh Tyagi v. Jaibir Singh (FAO No. 842/2003) in which matters the Hon’ble High Court laid out the procedure to be followed by the Motor Accidents Claims Tribunals established in Delhi, providing inherent safeguards to keep a check on fraudulent claims.

Q. Last month, the Madurai bench of the Madras High Court observed that it is high time the stakeholders had a rethink on fixing the driver of the big vehicle as a tortfeasor in cases of road accidents involving big and small vehicles. The bench pointed out that it may not always be right to hold the driver of the big vehicle responsible for the accident. As a lawyer with expertise in cases pertaining to the Motor Vehicles Act, what is your reaction to this observation?

The issue identified by the Madras High Court is a pertinent institutional issue. In a case where death has occurred, the attitude of all stakeholders is influenced by the thought of a likely economic crisis which the family of deceased is likely to face. Since, it is a rarity that a bigger vehicle faces more damage, leave apart death, the issue identified by the Madras High Court comes into play. In fact, I have come across cases in which despite it being documented that deceased motorcycle rider had alcoholic breath and was not wearing a helmet, the driver of the car was prosecuted to give an opportunity to the family of deceased motorcycle rider to get compensation under the Motor Vehicles Act, 1988. The Supreme Court of India, in several matters, has identified and addressed the issue of non-prosecution of traffic violations but it is yet to give guidance for adopting a tougher stance qua issue of accountability for contributory negligence in motor accident cases by Courts.

Q. Recently, a plea was filed in the Delhi High Court challenging the constitutional validity of Section 14(1)(h) of Delhi Rent Control Act, 1958. It said the DRCA is biased in favour of tenants, and in the present day the tenant-landlord dynamics are not the same as they were in the years after independence. The HC issued notice on this plea. What is your opinion on the plea’s contention?

The Delhi Rent Control Act, 1958 (“DRCA”) was enacted to protect those tenants who were victim of partition and had to re-establish their family in Delhi. DRCA, as legislated, dealt only with residential properties. This position was, however, changed by the Supreme Court of India, by exercise of jurisdiction under Article 142 of Constitution of India, in Satyawati Sharma (Dead) By Lrs v. Union of India (Civil Appeal No. 1897 of 2003) in which the Supreme Court dealt with a challenge to Section 14(1)(e) of Delhi Rent Control Act in relation to a property which was residential in character but was rented for a commercial purpose. The plea qua Section 14(1)(h) of DRCA seeks an extension of the same principle as laid down in Satyawati Sharma (Supra). It would be wrong to state that DRCA is biased in favor of tenants, as protection of tenants was the very purpose of enactment of DRCA. It might be justified to say that DRCA has served its purpose.

Q. What advice would you give to lawyers who want to crack the AOR exam?

The AOR exam is very difficult to crack. On account of lapse of five years or more since graduation, one loses the ability to study and attempt / write lengthy examinations, which itself becomes a hurdle. I found it more difficult for myself since I was spending most of my time before the District Courts in Delhi. Since it needs weeks (if not months) to prepare, I would suggest to the aspirants to put technology to use and keep the reading material for AOR examinations on Kindle and / or I-pad or any other tablet, to read whenever they get time every now and then. Further, aspirants can consider copying relevant paragraphs from judgments on rough paper as it would not only help in creating a memory as to what the particular judgment states but also make their writing speed better.

Q. Considering the disruption caused by the Covid-19 pandemic in the functioning of courts, in your opinion what kind of technological upgrade is required to ensure uninterrupted and efficient functioning of the courts and of lawyers’ practice?

The pre-covid judicial system faced many issues which, inter-alia, included massive consumption of paper and ever-increasing footfall in Courts. This pandemic created a necessity which compelled the Courts to address both these issues. In my opinion, the hybrid system via VC hearing should be incorporated as part of the system as such, at least for basic miscellaneous hearings. Every day many matters are listed for miscellaneous work or procedural applications which can be easily addressed via VC hearing. As regards E-filing, it is an apposite step for a simple reason that at least the wastage of paper in effecting service via different modes is prevented. What is needed is an upgradation in IT infrastructure available with the District Courts to enable effective and smooth functioning of hybrid system via VC hearing.

Q. Do you think Artificial Intelligence and legal technology in legal research can be helpful in improving the efficiency of the judicial system?

Yes. Legal research is a time-consuming job. It is something every role-player i.e. lawyer, judge & academician, has to do independently. It is, therefore, imperative that every effort is made to reduce the time period taken to consume the same. Artificial Intelligence can go a long way in doing that.

****

Anubhab Sarkar is the Founding Partner at Triumvir Law which he started three years ago at the age of 26. Triumvir Law specialises in the field of International Dispute Resolution. Anubhab advises and aids clients in high stakes international dispute resolution matters and corporate-commercial transactions. He also runs a separate pro-bono research wing focussing on climate change.

Q. Could you tell us about Triumvir Law and the firm’s key practice areas?

Triumvir Law is a boutique law firm based mainly out of Bangalore and Mumbai.

As a team of millennials, we try to use technology, teamwork, organisational skills, and uninhibited communication as efficiently as we can to take on complex legal problems and to deliver the best to our clients, whom we regard with the utmost care and respect. We provide a wide array of services in the fields of corporate and commercial laws, dispute resolution, and intellectual property, to name a few. Our main focus, however, remains International Commercial Arbitration and Bilateral Investment Treaty advisory. Additionally, we hand-hold start-ups through the initial stages of setting up their businesses while simultaneously identifying and advising them about potential legal risks. Essentially, we work in various areas of law depending upon the needs of our clients. We also have a strong consultancy chain based out of many cities (including some abroad) that we do not directly operate out of. Therefore, in the event that a client requires immediate legal advice pertaining to another jurisdiction, we are able to connect the client to another lawyer operating therein.

We also a run a separate pro-bono research wing on climate change and forced migration. We believe that climate change is an alarming reality and that we, as lawyers, can significantly help address the concerns that it poses. On this basis, we are creating a task force from all walks of life in order to help us build a community to tackle climate change in all ways possible.

Q. What sort of cases do you handle? Can you share any memorable case with us?

I work extensively in the practice areas of Arbitration, Corporate Commercial, and Foreign Investment Laws. But I have also been involved, lately, in corporate transactions focused on the technology industry including Cross-Border Mergers & Acquisitions.

Every project we take on is memorable in some way or the other. If I had to choose, however, I believe one of our latest International Commercial Arbitration projects has proven to be a truly memorable experience. We appeared on behalf of a respondent in a high-stakes multi-party international arbitration in which we were faced with an incredibly competent and experienced team of lawyers. Before the pandemic, we travelled back and forth between three cities for the case, and had countless sleepless nights in between. The transition to virtual arbitration sessions was particularly memorable too. At the end of it all, leaving a courtroom or arbitration hearing (virtual or not!), with the knowledge that you have successfully defended your client against the most capable of opponents, is an incomparable feeling – and that’s what makes it all worth it.

A particularly notable landmark in our journey was our first investment treaty arbitration mandate. While starting out, it was unimaginable that we would have the chance to represent a large Indian conglomerate in an investment treaty claim against a South Asian state. And yet, at the age of 27, I was given this opportunity. We were handling an incredibly complex dispute and were up against opposing counsel comprising established members of the bar. Till date, I consider this to be among my biggest achievements.

Q. What is the scope of International Arbitration in India?

India has always been an attractive destination for foreign investment. However, foreign companies were historically sceptical about choosing India as their seat of arbitration on account of the hitherto prevailing uncertainty regarding arbitral procedures and enforcement of foreign arbitral awards. In 2015, the Government of India took a noteworthy step towards the goal of making India an arbitration-friendly jurisdiction by introducing the Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2015 to amend the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (“the Arbitration Act”); later, the Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019 to the same; and now, the newly released Ordinance of 2020. There is also now a gradual trend towards institutional arbitration, with the growth of centres such as the Mumbai Centre for International Arbitration (MCIA) and the prospective New Delhi International Arbitration Centre. Things are certainly getting better, with the Supreme Court in fact recently referring two cases to the MCIA for institutional arbitration.

While significant measures are being taken to make India a favourable forum for international arbitration, and to mould the judicial framework into better upholding party autonomy, there is still a long way to go. However, I strongly believe that the golden age for Indian arbitration is right on the horizon, and India will certainly grow to be an integral part of international arbitration history.

Q. You have had the opportunity of interning with the International Arbitration team at Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer and the Essex Court Chambers. What do you have to say about the Arbitration mechanism in India and its comparisons to other countries?

In my first year in law school, I made it my ambition to explore public international law, which soon led me to the fascinating world of international arbitration. I shaped my activities, time, and efforts in law school accordingly – acting as Research Assistant to Professor Martin Hunter at Essex Court Chambers and interning at Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer ended up being among the most formative experiences of my life. Apart from observing an extremely professional and inspiring work ethic, I had the opportunity to gain unparalleled international exposure by interacting with some of my idols – who, coincidentally, are also luminaries of the profession. I learned about so much more than simply work and the law, and that is something I consider priceless in my growth as a lawyer and a human being.

Regarding the Indian Arbitration framework, I believe that we are quickly moving towards a new institutional arbitration-friendly regime. However, with respect to Investment Arbitration, we are still a long way from becoming an encumbrance free jurisdiction. With India’s refusal to ratify the ICSID Convention, and also its recent termination of around 58 BITs and replacement thereof with a new Model BIT, it would appear that radical policy changes need to be effected in order to inspire and strengthen the faith of foreign investors in the Indian market and induct our economy into a global ISDS regime.

Q. During your college days, you participated in a lot of moot court competitions. How important do you think is mooting for law students?

I was passionate about mooting from the beginning of my time at law school. I believe that mooting is one of the few activities in law school which truly prepares you for the outside world. Your research skills, strategy, communication, and ability to handle yourself under pressure is rigorously tested – and that is precisely what the profession demands from you. Even though it might be an overwhelming experience initially, learn to enjoy the thrill of it and keep yourself calm. Remember that the judge, too, was once in your position. Comb through your proposition multiple times – the hidden details may often be the key to your issues – and ensure that you are clear with the facts and applicable law. Employ a constructive and strategic approach to the problem, and do some background reading on the general position of law as well as the specifics of your issue. Teamwork is in fact among the most important part of mooting – learn to communicate effectively and honestly with your teammates, and you will be good to go.

Q. What are your views on the role of artificial intelligence and legal technology being adopted to enhance the legal future?

The role of Artificial Intelligence in our lives, and particularly in that of a lawyer, has increased exponentially. From basic task management and scheduling of meetings – hail Google Calendar! – to conducting operations online such as legal research and due diligence, AI has been a godsend for legal professionals. In the Indian legal sector, I believe there is still much scope for further integration of AI into our daily legal processes, with contract review, document automation, electronic discovery, and more. In the Arbitration world, specifically, Arbitrator Intelligence is revolutionizing the way counsels approach international arbitration cases. Their efficient system of research and feedback on arbitrators, which is then compiled into arbitrator reports – enables lawyers to mould their strategy according to the tribunal they are arguing before.

On a more fundamental level, our firm is using MS Teams to facilitate our transfer from a physical workspace to a virtual one at the start of the pandemic. Despite a few small hiccups, there have been several benefits – we have become more efficient with our functioning, communication, and resourcing. We are also slowly able to maintain a better work-life balance, and also connect with interns from across India, who may not have been able to come to Bangalore and work with us before.

In my opinion, the belief that AI poses a threat to the existence of lawyers is misplaced and rather exaggerated. While AI holds tremendous potential to revolutionise the way lawyers operate, making us more efficient and accurate, it can never replace the humanity which forms the bedrock of the legal profession.

Q. According to you, what are the pros and cons of Online Dispute Resolution?

ODR, in my opinion, has the scope to usher in a new era for Indian dispute resolution on both domestic and global fronts. Concerns around distance and travelling are effectively dispelled as the mediators and parties can connect at any time from any corner of the world; parties and lawyers can move between virtual rooms at a click of a button while simultaneously having a guided, productive discussion. An irrefutable advantage of ODR, additionally, is the cost and time effectiveness for all stakeholders – parties will now bear minimal costs, and also virtually eliminate long waiting hours/multiple adjournments. Another notable change that ODR will bring is the minimising of in-person confrontation, which curtails chances of any emotional overhauls – an otherwise fairly regular feature of direct mediation sessions.

It does, however, have its fair share of cons. Party confidentiality stands at a constant risk with virtual hearings capable of being recorded. Infrastructural disparity between parties and lawyers could put one at an undue disadvantage or create more encumbrances in the proceedings as compared to in-person hearings. Such disparities may also, at times, create an exclusive environment similar to denial of access to justice for certain stakeholders. The in-person human element is lost, which can sometimes be the key to resolving a dispute.

As a nation making leaps forward in the work from home/ODR regime, India needs to strategically direct investments towards making structural changes that facilitate infrastructure and accessibility across the country. Clear and stringent regulation for data safety and confidentiality are the need of the hour, with hearings and document exchanges moving online. Most importantly, the judicial system must work towards inspiring the confidence of the international community in our legal system by ensuring unencumbered accessibility for all parties involved.

With institutions such as the LCIA giving formal recognition and encouragement to ODR, other international bodies will soon follow suit, simplifying the ADR process even further.

Q. How do you stay up-to date with all the latest legal developments?

The legal industry is constantly evolving. Between firm mergers, court cases, politics, policy and international relations, not a day passes by without a legal issue making news. To stay up to date with such developments, I have access to prominent international commercial arbitration and dispute resolution journals/databases, and also follow Supreme Court developments regularly. News apps and legal blogs are also very useful resources for such updates. Personally, I prefer to be engaged even when I’m on the move – podcasts often help me in this endeavour, since I learn and absorb better while listening rather than reading.

Apart from the above, our internship program encourages interns to develop the habit of keeping track with relevant legal developments, wherein they regularly compile corporate law and arbitration updates on a daily or weekly basis. These updates also serve as excellent resources for me and the entire team.

****

Ms. Shivani Luthra Lohiya is a practicing Advocate in New Delhi. She graduated from Amity Law School, Delhi and then went on to do an LLM from the University of Pennsylvania Law School and an M.Phil in Criminology from the University of Cambridge. Ms. Lohiya has had an independent practice since 2018 and has recently started a Chamber by the name of Law Chambers of Saluja and Luthra Lohiya. She has a keen interest in criminal law, commercial litigation and arbitration along with other allied laws.

Ms Lohiya, along with other women lawyers, had on January 18 moved the Supreme Court challenging the resumption of physical hearings in the Delhi High Court contending that they were not given the choice to argue cases virtually. On January 22, the Delhi High Court said it has initiated steps for a hybrid system where a hearing can be joined through virtual as well as physical mode. The high court issued an administrative order stating that when a particular bench is conducting virtual hearing, a lawyer may opt for the virtual hearing of a matter by giving prior intimation.

Q. Why did you decide to file this petition against resumption of physical hearings in the Delhi High Court?

The fact is that the threat of Covid is still very much there. A lot of us lawyers live with parents with comorbidities, many lawyers have children, some themselves live with comorbidities. We all know people who have lost their lives due to the pandemic. Schools are still not open and many lawyers have small children and someone has to be there at home with their children to help them with their virtual schooling. These were the major concerns.

Now that we have waited for nine months for the courts to reopen, another two or three months would not be the end of the world. We can’t at this point be asked to choose between our right to practice, and our duty towards our parents or our children.

Looking at all these facts, the petition was filed. The larger reason was the health concerns. None of us chose litigation to sit behind computers and argue. We don’t want virtual hearings to become a permanent fixture unless it is procedural in the path of progress. But, at the same time, we need to be aware of the realities. Covid still does not have a cure, nor is the vaccine readily available.

Q. Some lawyers have claimed that virtual hearings are creating hurdles in their work and that they want physical hearings to resume so that they can earn a living. How would you respond to this argument?

Of course virtual hearings have created hurdles for many lawyers. A lot of people are not technologically savvy. Many of our senior lawyers had to learn how to use this technology. There are also many people who do not have access to such technology. That’s why we suggested a hybrid system, where lawyers can choose whether they want to argue virtually or by being physically present in the court room.

Physical hearings are unnecessarily burdensome on the judges during these times as well, as they have to go (when many others are present in court). Many judges are also in the high-risk category. They may have comorbidities. While it is true that in the courts there are screens to protect the judges from any direct interaction, and the judges sit far away (from the others), however, there is some interaction of the public with the court staff, who in turn interact closely with judges.

The Delhi High Court is hearing only urgent matters. I don’t understand at this point what physically opening up the High Court will achieve when you’re not increasing the number of matters that are being heard. Reverting to the physical system will not help lawyers who are not having sufficient work. If I have to file an application in a pending matter today, I have to show some urgency. It’s not that matters are getting listed or taken up in regular course like they were before. Consequently, the virtual hearing system being done away with without increasing the number of cases, I don’t see how it would improve the plight of the lawyers who want to go physically.

Another concern, which is not part of the petition, was that a lot people were looking at virtual hearings as the way forward. The courts have come up with some technological advancement. There is a mechanism to conduct hearings via video conferencing and the platform has been working quite well for arguments. I don’t think it has been causing too much of a problem if you have access to the internet. The courts have also established areas within the court complexes itself where people can access this technology. Ultimately, we’re all doing our meetings over video conferencing as well.

Virtual hearings may actually lead to a more efficient system of Courts’ function. For instance, under normal circumstances very often we have to take a date in one Court because we are physically appearing in another Court. Transport takes time. But this is something for the Courts to consider in the future. That’ll depend on the Court’s discretion. For now, the petition simply said that Covid has not gone.

Q. A lot of subordinate courts in small cities and towns don’t have the technology that’s available in courts in the metro cities to hold virtual court functions. In a post-covid world, do you think virtual courts are sustainable in the long run?

In my opinion, sustainability (of virtual courts) in the long run is a question mark. It’s a way forward, I think. But whether or not it can be a permanent fixture… at this point there’s lack of (internet) connectivity as well. Not just lawyers, but litigants also may not have access to the technology. And many litigants physically go into the courts to find lawyers.

There’s nothing wrong with virtual hearings. It’s not that we’re not getting relief, or that judges are not able to understand what’s going on, or that we’re not able to hear each other or understand each other. Yes, there are glitches. Sometimes there’s an internet problem that causes the voice to break, sometimes you’re not unmuted when you have to speak and you’re trying to frantically call the court master saying can you please unmute us. So, there are certain disadvantages as well. But there are advantages which cannot be overlooked. You have to weigh the two. And it’s for the Courts to decide if virtual hearings are sustainable or not in the long run. In my opinion, I think it could be worked out. But it would require a very phased manner of implementation. It just cannot happen overnight. Physical hearings for accused in custody for remand matters are important in the long run and for clients in custody to meet their lawyers when normalcy returns. We’ll have to keep all the realities of the country in check — the level of education, the technology, the support being given by the government. It’s a long-term goal.

In fact, virtual hearings have enabled a lot of people, especially women, to juggle their work and childcare or household responsibilities. I have met women who have had to leave practice temporarily after having children and rejoined after some years. Perhaps they wouldn’t have if there was the option of virtual hearings at that time.

Q. So would you say that promoting technology in the courts especially virtual hearings can lead to gender inequality in the long run?

That’s an argument people are using, but I won’t go so far as to say gender equality. I think women in litigation have to prove themselves just like any other man. We may have certain additional obstacles, but that doesn’t mean men don’t have any obstacles and that it’s a cakewalk for them.

Q. Do you think some kind of a gender bias exists in the legal profession, like in many other professions, and that women lawyers have to work harder than men to prove themselves, even though men may have their own share of problems?

I think to some extent, yes. But it’s also because of the role of women in society that exists in people’s minds. It’s less to do with the profession and more to do with the mindset of people. It’s not that the profession is not meant for women.

Q. How has the pandemic affected you personally — as a lawyer, and as a woman?

I do a lot of criminal law, particularly criminal trials and trials have not been taking place, evidence was not being recorded. Professionally, it has greatly affected me in that sense. Personally, I have older people and senior citizens in my home so I’ve had to be extremely careful throughout the pandemic. Some of my close friends have lost family members to Covid. That, of course, is a hazard of this pandemic that everyone is facing. It has been a blessing to have the judiciary balance the needs of the lawyers as well as the litigants by introducing a system of virtual hearings in the first place and thereafter, by considering introducing a hybrid system, giving an option to lawyers to appear through virtual / physical hearing.

****

Vibhanshu Srivastava specializes in dispute resolution and has diverse experience in handling a vast array of Litigation and Alternative Dispute Resolution matters arising out of corporate/commercial transactions, tender-preconditions and terms, winding up of a company, oppression and mismanagement, intellectual property disputes and real-estate dealings. He advises clients on formulating effective strategies for dispute resolution and appears frequently in the Supreme Court, various High Courts, Commercial and Arbitral Tribunals and Consumer Courts.