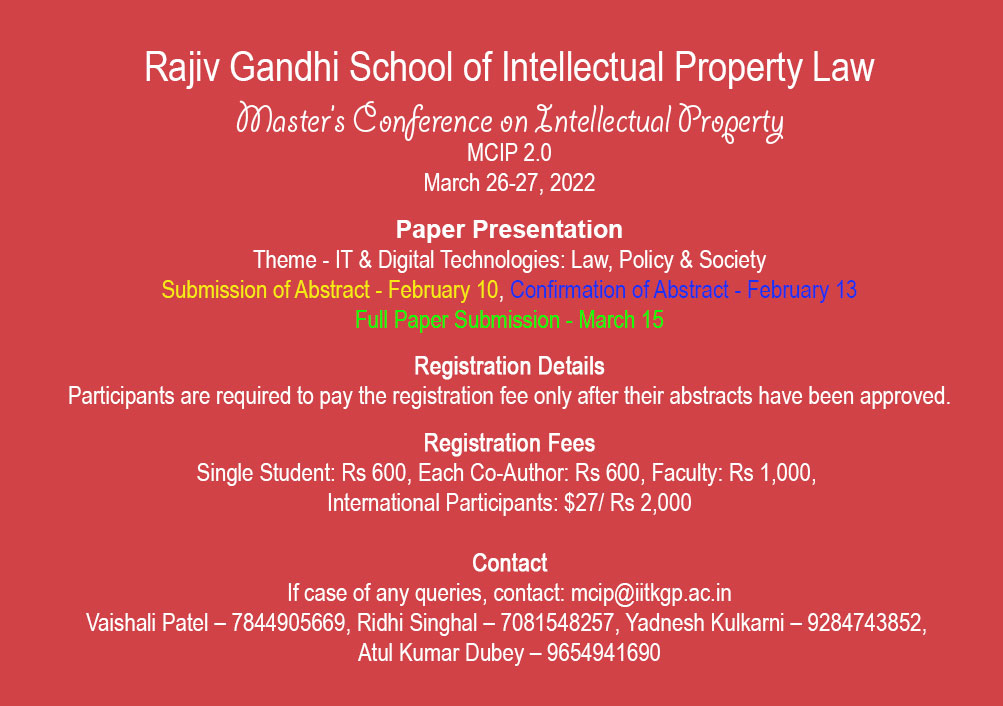

Hidayatullah National Law University, Raipur, in collaboration with the Tribal Research and Training Institute and Thakur Pyarelal State Institute of Panchayat and Rural Development, Government of Chhattisgarh, is organizing (in virtual mode) the Two-day National Conference on Tribal Transition in India: Issues, Challenges and the Road Ahead.

Details of the Valedictory Ceremony-

Date: 27th November, 2021

Time: 5:00 PM-6:30 PM

Hidayatullah National Law University, Raipur, in collaboration with the Tribal Research and Training Institute and Thakur Pyarelal State Institute of Panchayat and Rural Development, Government of Chhattisgarh, is organizing (in virtual mode) the Two-day National Conference on Tribal Transition in India: Issues, Challenges and the Road Ahead.

Details of the Inaugural Ceremony-

Date: 26th November, 2021

Time: 10:00 AM -11:30 AM

Link for Registration : https://forms.gle/9j5aNXdNdqwzux8Z7

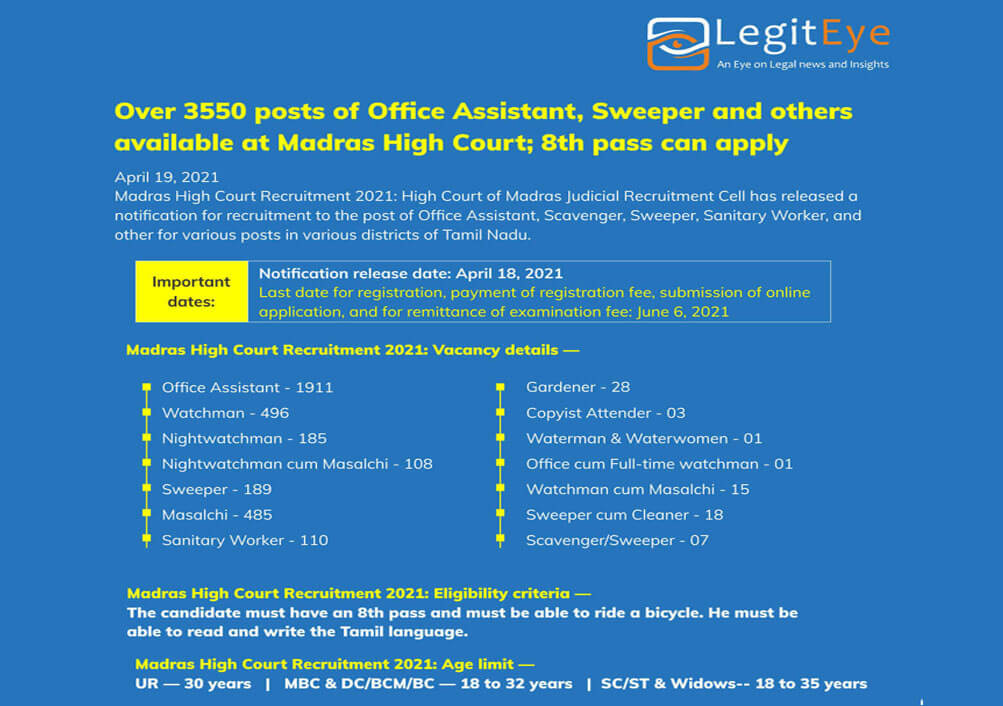

Access Official Notification Link here: https://jrchcm.onlineregistrationform.org/MHCMP/districtList.jsp

Access Direct Link to Apply here: https://jrchcm.onlineregistrationform.org/MHCMP/

India Law Offices LLP (ILO) is hosting a webinar to discuss relevance of mediation in delivering justice in India and how this unique tool has turned out to be most potent in the armouries of ADR processes especially during current global crisis.

Webinar Details:

Agenda: Role of Mediation in Justice Delivery System

Speakers: Hon’ble Mr. Justice G.S. Sistani (Judge (Retd.) High Court of Delhi), Mr. Gautam Khurana (Managing Partner, ILO), Dr. Chandra Shekhar (Partner, ILO)

Timings: 9th December 2020, 5:00 PM – 6:00 PM (IST)

For Registration, please Click Here

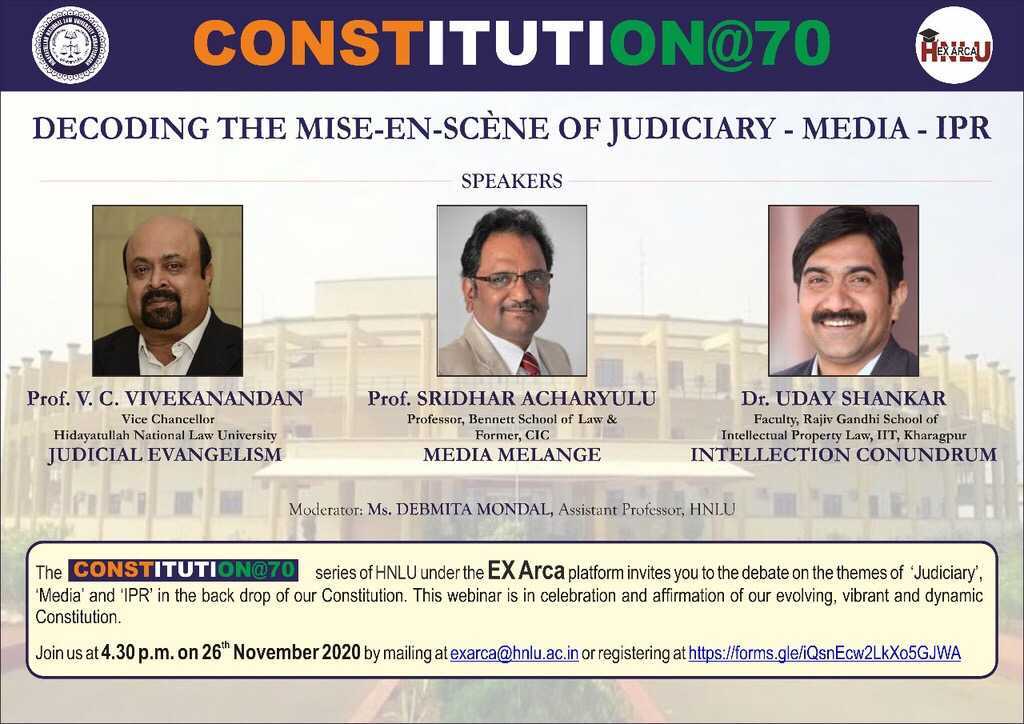

Date: 26th November, 2020

Time: 4:30 PM

Register at: exacra@hnlu.ac.in or https://forms.gle/iQsnEcw2LkXo5GJWA

Submission Deadline: 20th December, 2020

Date: 24-27 MARCH 2021

DEADLINE FOR SUBMISSIONS: 15 DECEMBER 2020

The teachers and research scholars desiring to participate in the conference can visit IPIRA website of http://ipresearchersasia.org/

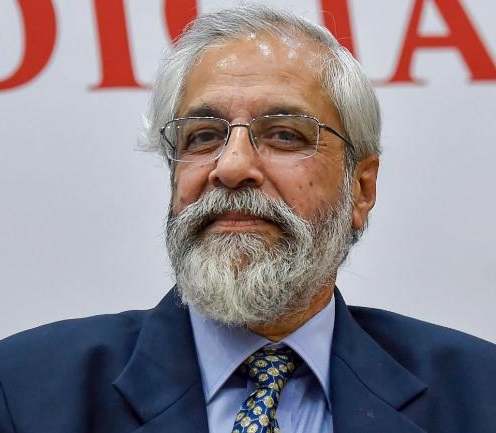

Time for judiciary to introspect and see what can be done to restore people’s faith – Justice Lokur

Justice Madan B Lokur, was a Supreme Court judge from June 2012 to December 2018. He is now a judge of the non-resident panel of the Supreme Court of Fiji. He spoke to LegitQuest on January 25, 2020.

Q: You were a Supreme Court judge for more than 6 years. Do SC judges have their own ups and downs, in the sense that do you have any frustrations about cases, things not working out, the kind of issues that come to you?

A: There are no ups and downs in that sense but sometimes you do get a little upset at the pace of justice delivery. I felt that there were occasions when justice could have been delivered much faster, a case could have been decided much faster than it actually was. (When there is) resistance in that regard normally from the state, from the establishment, then you kind of feel what’s happening, what can I do about it.

Q: So you have had the feeling that the establishment is trying to interfere in the matters?

A: No, not interfering in matters but not giving the necessary importance to some cases. So if something has to be done in four weeks, for example if reply has to be filed within four weeks and they don’t file it in four weeks just because they feel that it doesn’t matter, and it’s ok if we file it within six weeks how does it make a difference. But it does make a difference.

Q: Do you think this attitude is merely a lax attitude or is it an infrastructure related problem?

A: I don’t know. Sometimes on some issues the government or the establishment takes it easy. They don’t realise the urgency. So that’s one. Sometimes there are systemic issues, for example, you may have a case that takes much longer than anticipated and therefore you can’t take up some other case. Then that necessarily has to be adjourned. So these things have to be planned very carefully.

Q: Are there any cases that you have special memories of in terms of your personal experiences while dealing with the case? It might have moved you or it may have made you feel that this case is really important though it may not be considered important by the government or may have escaped the media glare?

A: All the cases that I did with regard to social justice, cases which concern social justice and which concern the environment, I think all of them were important. They gave me some satisfaction, some frustration also, in the sense of time, but I would certainly remember all these cases.

Q: Even though you were at the Supreme Court as a jurist, were there any learning experiences for you that may have surprised you?

A: There were learning experiences, yes. And plenty of them. Every case is a learning experience because you tend to look at the same case with two different perspectives. So every case is a great learning experience. You know how society functions, how the state functions, what is going on in the minds of the people, what is it that has prompted them to come the court. There is a great learning, not only in terms of people and institutions but also in terms of law.

Q: You are a Judge of the Supreme Court of Fiji, though a Non-Resident Judge. How different is it in comparison to being a Judge in India?

A: There are some procedural distinctions. For example, there is a great reliance in Fiji on written submissions and for the oral submissions they give 45 minutes to a side. So the case is over within 1 1/2 hours maximum. That’s not the situation here in India. The number of cases in Fiji are very few. Yes, it’s a small country, with a small number of cases. Cases are very few so it’s only when they have an adequate number of cases that they will have a session and as far as I am aware they do not have more than two or three sessions in a year and the session lasts for maybe about three weeks. So it’s not that the court sits every day or that I have to shift to Fiji. When it is necessary and there are a good number of cases then they will have a session, unlike here. It is then that I am required to go to Fiji for three weeks. The other difference is that in every case that comes to the (Fiji) Supreme Court, even if special leave is not granted, you have to give a detailed judgement which is not the practice here.

Q: There is a lot of backlog in the lower courts in India which creates a problem for the justice delivery system. One reason is definitely shortage of judges. What are the other reasons as to why there is so much backlog of cases in the trial courts?

A: I think case management is absolutely necessary and unless we introduce case management and alternative methods of dispute resolution, we will not be able to solve the problem. I will give you a very recent example about the Muzaffarpur children’s home case (in Bihar) where about 34 girls were systematically raped. There were about 17 or 18 accused persons but the entire trial finished within six months. Now that was only because of the management and the efforts of the trial judge and I think that needs to be studied how he could do it. If he could do such a complex case with so many eyewitnesses and so many accused persons in a short frame of time, I don’t see why other cases cannot be decided within a specified time frame. That’s case management. The second thing is so far as other methods of disposal of cases are concerned, we have had a very good experience in trial courts in Delhi where more than one lakh cases have been disposed of through mediation. So, mediation must be encouraged at the trial level because if you can dispose so many cases you can reduce the workload. For criminal cases, you have Plea Bargaining that has been introduced in 2009 but not put into practice. We did make an attempt in the Tis Hazari Courts. It worked to some extent but after that it fell into disuse. So, plea bargaining can take care of a lot of cases. And there will be certain categories of cases which we need to look at carefully. For example, you have cases of compoundable offences, you have cases where fine is the punishment and not necessarily imprisonment, or maybe it’s imprisonment say one month or two month’s imprisonment. Do we need to actually go through a regular trial for these kind of cases? Can they not be resolved or adjudicated through Plea Bargaining? This will help the system, it will help in Prison Reforms, (prevent) overcrowding in prisons. So there are a lot of avenues available for reducing the backlog. But I think an effort has to be made to resolve all that.

Q: Do you think there are any systemic flaws in the country’s justice system, or the way trial courts work?

A: I don’t think there are any major systemic flaws. It’s just that case management has not been given importance. If case management is given importance, then whatever systematic flaws are existing, they will certainly come down.

Q; And what about technology. Do you think technology can play a role in improving the functioning of the justice delivery system?

I think technology is very important. You are aware of the e-courts project. Now I have been told by many judges and many judicial academies that the e-courts project has brought about sort of a revolution in the trial courts. There is a lot of information that is available for the litigants, judges, lawyers and researchers and if it is put to optimum use or even semi optimum use, it can make a huge difference. Today there are many judges who are using technology and particularly the benefits of the e-courts project is an adjunct to their work. Some studies on how technology can be used or the e-courts project can be used to improve the system will make a huge difference.

Q: What kind of technology would you recommend that courts should have?

A: The work that was assigned to the e-committee I think has been taken care of, if not fully, then largely to the maximum possible extent. Now having done the work you have to try and take advantage of the work that’s been done, find out all the flaws and see how you can rectify it or remove those flaws. For example, we came across a case where 94 adjournments were given in a criminal case. Now why were 94 adjournments given? Somebody needs to study that, so that information is available. And unless you process that information, things will just continue, you will just be collecting information. So as far as I am concerned, the task of collecting information is over. We now need to improve information collection and process available information and that is something I think should be done.

Q: There is a debate going on about the rights of death row convicts. CJI Justice Bobde recently objected to death row convicts filing lot of petitions, making use of every legal remedy available to them. He said the rights of the victim should be given more importance over the rights of the accused. But a lot of legal experts have said that these remedies are available to correct the anomalies, if any, in the justice delivery. Even the Centre has urged the court to adopt a more victim-centric approach. What is your opinion on that?

You see so far as procedures are concerned, when a person knows that s/he is going to die in a few days or a few months, s/he will do everything possible to live. Now you can’t tell a person who has got terminal cancer that there is no point in undergoing chemotherapy because you are going to die anyway. A person is going to fight for her/his life to the maximum extent. So if a person is on death row s/he will do everything possible to survive. You have very exceptional people like Bhagat Singh who are ready to face (the gallows) but that’s why they are exceptional. So an ordinary person will do everything possible (to survive). So if the law permits them to do all this, they will do it.

Q: Do you think law should permit this to death row convicts?

A: That is for the Parliament to decide. The law is there, the Constitution is there. Now if the Parliament chooses not to enact a law which takes into consideration the rights of the victims and the people who are on death row, what can anyone do? You can’t tell a person on death row that listen, if you don’t file a review petition within one week, I will hang you. If you do not file a curative petition within three days, then I will hang you. You also have to look at the frame of mind of a person facing death. Victims certainly, but also the convict.

Q: From the point of jurisprudence, do you think death row convicts’ rights are essential? Or can their rights be done away with?

A: I don’t know you can take away the right of a person fighting for his life but you have to strike a balance somewhere. To say that you must file a review or curative or mercy petition in one week, it’s very difficult. You tell somebody else who is not on a death row that you can file a review petition within 30 days but a person who is on death row you tell him that I will give you only one week, it doesn’t make any sense to me. In fact it should probably be the other way round.

Q: What about capital punishment as a means of punishment itself?

A: There has been a lot of debate and discussion about capital punishment but I think that world over it has now been accepted, more or less, that death penalty has not served the purpose for which it was intended. So, there are very few countries that are executing people. The United States, Saudi Arabia, China, Pakistan also, but it hasn’t brought down the crime rate. And India has been very conservative in imposing the death penalty. I think the last 3-4 executions have happened for the persons who were terrorists. And apart from that there was one from Calcutta who was hanged for rape and murder. But the fact that he was hanged for rape and murder has not deterred people (from committing rape and murder). So the accepted view is that death penalty has not served the purpose. We certainly need to rethink the continuance of capital punishment. On the other hand, if capital punishment is abolished, there might be fake encounter killings or extra judicial killings.

Q: These days there is the psyche among people of ‘instant justice’, like we saw in the case of the Hyderabad vet who was raped and murdered. The four accused in the case were killed in an encounter and the public at large and even politicians hailed it as justice being delivery. Do you think this ‘lynch mob mentality’ reflects people’s lack of faith in the justice system?

A: I think in this particular case about what happened in Telangana, investigation was still going on. About what actually happened there, an enquiry is going on. So no definite conclusions have come out. According to the police these people tried to snatch weapons so they had to be shot. Now it is very difficult to believe, as far as I am concerned, that 10 armed policeman could not overpower four unarmed accused persons. This is very difficult to believe. And assuming one of them happened to have snatched a (cop’s) weapon, maybe he could have been incapacitated but why the other three? So there are a lot of questions that are unanswered. So far as the celebrations are concerned, the people who are celebrating, do they know for certain that they (those killed in the encounter) were the ones who did the crime? How can they be so sure about it? They were not eye witnesses. Even witnesses sometimes make mistakes. This is really not a cause for celebration. Certainly not.

Q: It seems some people are losing their faith in the country’s justice delivery system. How to repose people’s faith in the legal process?

A: You see we again come back to case management and speedy justice. Suppose the Nirbhaya case would have been decided within two or three years, would this (Telangana) incident have happened? One can’t say. The attack on Parliament case was decided in two or three years but that has not wiped out terrorism. There are a lot of factors that go into all this, so there is a need to find ways of improving justice delivery so that you don’t have any extremes – where a case takes 10 years or another extreme where there is instant justice. There has to be something in between, some balance has to be drawn. Now you have that case where Phoolan Devi was gangraped followed by the Behmai massacre. Now this is a case of 1981, it has been 40 years and the trial court has still not delivered a judgement. It’s due any day now, (but) whose fault is that. You have another case in Maharashtra that has been transferred to National Investigating Agency two years after the incident, the Bhima-Koregaon case. Investigation is supposedly not complete after two years also. Whose fault is that? So you have to look at the entire system in a holistic manner. There are many players – the investigation agency is one player, the prosecution is one player, the defence is one player, the justice delivery system is one player. So unless all of them are in a position to coordinate… you cannot blame only the justice delivery system. If the Telangana police was so sure that the persons they have caught are guilty, why did they not file the charge sheet immediately? If they were so sure the charge sheet should have been filed within one day. Why didn’t they do it?

Q: At the trial level, there are many instances of flaws in evidence collection. Do you think the police or whoever the investigators are, do they lack training?

A: Yes they do! The police lacks training. I think there is a recent report that has come out last week which says very few people (in the police) have been trained (to collect evidence).

Q: You think giving proper training to police to prepare a case will make a difference?

A: Yes, it will make a difference.

Q: You have a keen interest in juvenile justice. Unfortunately, a lot of heinous crimes are committed by juveniles. How can we correct that?

A: You see it depends upon what perspective we are looking at. Now these heinous crimes are committed by juveniles. Heinous crimes are committed by adults also, so why pick upon juveniles alone and say something should be done because juveniles are committing heinous crimes. Why is it that people are not saying that something should be done when adults are committing heinous crimes? That’s one perspective. There are a lot of heinous crimes that are committed against juveniles. The number of crimes committed against juveniles or children are much more than the crimes committed by juveniles. How come nobody is talking about that? And the people committing heinous crimes against children are adults. So is it okay to say that the State has imposed death penalty for an offence against the child? So that’s good enough, nothing more needs to be done? I don’t think that’s a valid answer. The establishment must keep in mind the fact that the number of heinous crimes against children are much more than those committed by juveniles. We must shift focus.

Q: Coming to NRC and CAA. Protests have been happening since December last year, the SC is waiting for the Centre’s reply, the Delhi HC has refused to directly intervene. Neither the protesters nor the government is budging. How do we achieve a breakthrough?

A: It is for the government to decide what they want to do. If the government says it is not going to budge, and the people say they are not going to budge, the stalemate could continue forever.

Q: Do you think the CAA and the NRC will have an impact on civil liberties, personal liberties and people’s rights?

A: Yes, and that is one of the reasons why there is protest all over the country. And people have realised that it is going to happen, it is going to have an impact on their lives, on their rights and that’s why they are protesting. So the answer to your question is yes.

Q: Across the world and in India, we are seeing an erosion of the value system upholding rights and liberties. How important is it for the healthy functioning of a country that social justice, people’s liberties, people’s rights are maintained?

A: I think social justice issues, fundamental rights are of prime importance in our country, in any democracy, and the preamble to our Constitution makes it absolutely clear and the judgement of the Supreme Court in Kesavananda Bharati and many other subsequent judgments also make it clear that you cannot change the basic structure of the Constitution. If you cannot do that then obviously you cannot take away some basic democratic rights like freedom of assembly, freedom of movement, you cannot take them away. So if you have to live in a democracy, we have to accept the fact that these rights cannot be taken away. Otherwise there are many countries where there is no democracy. I don’t know whether those people are happy or not happy.

Q: What will happen if in a democracy these rights are controlled by hook or by crook?

A: It depends upon how much they are controlled. If the control is excessive then that is wrong. The Constitution says there must be a reasonable restriction. So reasonable restriction by law is very important.

Q: The way in which the sexual harassment case against Justice Gogoi was handled was pretty controversial. The woman has now been reinstated in the Supreme Court as a staffer. Does this action of the Supreme Court sort of vindicate her?

A: I find this very confusing you know. There is an old joke among lawyers: Lawyer for the petitioner argued before the judge and the judge said you are right; then the lawyer for the respondent argued before the judge and the judge said you’re right; then a third person sitting over there says how can both of them be right and the judge says you’re also right. So this is what has happened in this case. It was found (by the SC committee) that what she said had no substance. And therefore, she was wrong and the accused was right. Now she has been reinstated with back wages and all. I don’t know, I find it very confusing.

Q: Do you think the retirement age of Supreme Court Judges should be raised to 70 years and there should be a fixed tenure?

A: I haven’t thought about it as yet. There are some advantages, there are some disadvantages. (When) You have extended age or life tenure as in the United States, and the Supreme Court has a particular point of view, it will continue for a long time. So in the United States you have liberal judges and conservative judges, so if the number of conservative judges is high then the court will always be conservative. If the number of liberal judges is high, the court will always be liberal. There is this disadvantage but there is also an advantage that if it’s a liberal court and if it is a liberal democracy then it will work for the benefit of the people. But I have not given any serious thought onthis.

Q: Is there any other thing you would like to say?

A: I think the time has come for the judiciary to sit down, introspect and see what can be done, because people have faith in the judiciary. A lot of that faith has been eroded in the last couple of years. So one has to restore that faith and then increase that faith. I think the judiciary definitely needs to introspect.

‘A major issue for startups, especially during fund raising, is their compliance with extant RBI foreign exchange regulations, pricing guidelines, and the Companies Act 2013.’- Aakash Parihar

Aakash Parihar is Partner at Triumvir Law, a firm specializing in M&A, PE/VC, startup advisory, international commercial arbitration, and corporate disputes. He is an alumnus of the National Law School of India University, Bangalore.

How did you come across law as a career? Tell us about what made you decide law as an option.

Growing up in a small town in Madhya Pradesh, wedid not have many options.There you either study to become a doctor or an engineer. As the sheep follows the herd, I too jumped into 11th grade with PCM (Physics, Chemistry and Mathematics).However, shortly after, I came across the Common Law Admission Test (CLAT) and the prospect of law as a career. Being a law aspirant without any background of legal field, I hardly knew anything about the legal profession leave alone the niche areas of corporate lawor dispute resolution. Thereafter, I interacted with students from various law schools in India to understand law as a career and I opted to sit for CLAT. Fortunately, my hard work paid off and I made it to the hallowed National Law School of India University, Bangalore (NSLIU). Joining NLSIU and moving to Bangalorewas an overwhelming experience. However, after a few months, I settled in and became accustomed to the rigorous academic curriculum. Needless to mention that it was an absolute pleasure to study with and from someof the brightest minds in legal academia. NLSIU, Bangalore broadened my perspective about law and provided me with a new set of lenses to comprehend the world around me. Through this newly acquired perspective and a great amount of hard work (which is of course irreplaceable), I was able to procure a job in my fourth year at law school and thus began my journey.

As a lawyer carving a niche for himself, tell us about your professional journey so far. What are the challenges that new lawyers face while starting out in the legal field?

I started my professional journey as an Associate at Samvad Partners, Bangalore, where I primarily worked in the corporate team. Prior to Samvad Partners, through my internship, I had developed an interest towards corporate law,especially the PE/VC and M&A practice area. In the initial years as an associate at Samvad Partners and later at AZB & Partners, Mumbai, I had the opportunity to work on various aspects of corporate law, i.e., from PE/VC and M&A with respect to listed as well as unlisted companies. My work experience at these firms equipped and provided me the know-how to deal with cutting edge transactional lawyering. At this point, it is important to mention that I always had aspirations to join and develop a boutique firm. While I was working at AZB, sometime around March 2019, I got a call from Anubhab, Founder of Triumvir Law, who told me about the great work Triumvir Law was doing in the start-up and emerging companies’ ecosystem in Bangalore. The ambition of the firm aligned with mine,so I took a leap of faith to move to Bangalore to join Triumvir Law.

Anyone who is a first-generation lawyer in the legal industry will agree with my statement that it is never easy to build a firm, that too so early in your career. However, that is precisely the notion that Triumvir Law wanted to disrupt. To provide quality corporate and dispute resolution advisory to clients across India and abroad at an affordable price point.

Once you start your professional journey, you need to apply everything that you learnt in law schoolwith a practical perspective. Therefore, in my opinion, in addition to learning the practical aspects of law, a young lawyer needs to be accustomed with various practices of law before choosing one specific field to practice.

India has been doing reallywell in the field of M&A and PE/VC. Since you specialize in M&A and PE/VC dealmaking, what according to you has been working well for the country in this sphere? What does the future look like?

India is a developing economy, andM&A and PE/VC transactions form the backbone of the same. Since liberalization, there has been an influx of foreign investment in India, and we have seen an exponential rise in PC/VA and M&A deals. Indian investment market growth especially M&A and PE/VC aspects can be attributed to the advent of startup culture in India. The increase in M&A and PE/VC deals require corporate lawyersto handle the legal aspects of these deals.

As a corporate lawyer working in M&A and PE/VC space, my work ranges from drafting term-sheets to the transaction documents (SPA, SSA, SHA, BTA, etc.). TheM&A and PE/VC deal space experienced a slump during the first few months of the pandemic, but since June 2021, there has been a significant growth in M&A and PE/VC deal space in India. The growth and consistence of the M&A and PE/VC deal space in India can be attributed to several factors such as foreign investment, uncapped demands in the Indian market and exceptional performance of Indian startups.

During the pandemic many businesses were shut down but surprisingly many new businesses started, which adapted to the challenges imposed by the pandemic. Since we are in the recovery mode, I think the M&A and PE/VC deal space will reach bigger heights in the comingyears. We as a firm look forward to being part of this recovery mode by being part of the more M&A and PE/VC deals in future.

You also advice start-ups. What are the legal issues or challenges that the start-ups usually face specifically in India? Do these issues/challenges have long-term consequences?

We do a considerable amount of work with startupswhich range from day-to-day legal advisory to transaction documentation during a funding round. In India, we have noticed that a sizeable amount of clientele approach counsels only when there is a default or breach, more often than not in a state of panic. The same principle applies to startups in India, they normally approach us at a stage when they are about to receive investment or are undergoing due diligence. At that point of time, we need to understand their legal issues as well as manage the demands of the investor’s legal team. The majornon-compliances by startups usually involve not maintaining proper agreements, delaying regulatory filings and secretarial compliances, and not focusing on proper corporate governance.

Another major issue for startups, especially during fund raising, is their compliance with extant RBI foreign exchange regulations, pricing guidelines, and the Companies Act 2013. Keeping up with these requirements can be time-consuming for even seasoned lawyers, and we can only imagine how difficult it would be for startups. Startups spend their initial years focusing on fund-raising, marketing, minimum viable products, and scaling their businesses. Legal advice does not usually factor in as a necessity. Our firm aims to help startups even before they get off the ground, and through their initial years of growth. We wanted to be the ones bringing in that change in the legal sector, and we hope to help many more such startups in the future.

In your opinion, are there any specific India-related problems that corporate/ commercial firms face as far as the company laws are concerned? Is there scope for improvement on this front?

The Indian legal system which corporate/commercial firms deal with is a living breathing organism, evolving each year. Due to this evolving nature, we lawyers are always on our toes.From a minor amendment to the Companies Act to the overhaul of the foreign exchange regime by the Reserve Bank of India, each of these changes affect the compliance and regulatory regime of corporates. For instance, when India changed the investment route for countries sharing land border with India,whereby any country sharing land border with India including Hong Kong cannot invest in India without approval of the RBI in consultation with the central government,it impacted a lot of ongoing transactions and we as lawyers had to be the first ones to inform our clients about such a change in the country’s foreign investment policy. In my opinion, there is huge scope of improvement in legal regime in India, I think a stable regulatory and tax regime is the need for the hour so far as the Indian system is concerned. The biggest example of such a market with stable regulatory and tax regime is Singapore, and we must work towards emulating the same.

Your boutique law firm has offices in three different cities — Delhi NCR, Mumbai and Bangalore. Have the Covid-induced restrictions such as WFH affected your firm’s operations? How has your firm adapted to the professional challenges imposed by the pandemic-related lifestyle changes?

We have offices in New Delhi NCR and Mumbai, and our main office is in Bangalore. Before the pandemic, our work schedule involved a fair bit of travelling across these cities. But post the lockdowns we shifted to a hybrid model, and unless absolutely necessary, we usually work from home.

In relation to the professional challenges during the pandemic, I think it was a difficult time for most young professionals. We do acknowledge the fact that our firm survived the pandemic. Our work as lawyers/ law firms also involves client outreach and getting new clients, which was difficult during the lockdowns. We expanded our client outreach through digital means and by conducting webinars, including one with King’s College London on International Treaty Arbitration. Further, we also focused on client outreach and knowledge management during the pandemic to educate and create legal awareness among our clients.

‘It’s a myth that good legal advice comes at prohibitive costs. A lot of heartburn can be avoided if documents are entered into with proper legal advice and with due negotiations.’ – Archana Balasubramanian

Archana Balasubramanian is the founding partner of Agama Law Associates, a Mumbai-based corporate law firm which she started in 2014. She specialises in general corporate commercial transaction and advisory as well as deep sectoral expertise across manufacturing, logistics, media, pharmaceuticals, financial services, shipping, real estate, technology, engineering, infrastructure and health.

August 13, 2021:

Lawyers see companies ill-prepared for conflict, often, in India. When large corporates take a remedial instead of mitigative approach to legal issues – an approach utterly incoherent to both their size and the compliance ecosystem in their sector – it is there where the concept of costs on legal becomes problematic. Pre-dispute management strategy is much more rationalized on the business’ pocket than the costs of going in the red on conflict and compliances.

Corporates often focus on business and let go of backend maintenance of paperwork, raising issues as and when they arise and resolving conflicts / client queries in a manner that will promote dispute avoidance.

Corporate risk and compliance management is yet another elephant in India, which in addition to commercial disputes can be a drain on a company’s resources. It can be clubbed under four major heads – labour, industrial, financial and corporate laws. There are around 20 Central Acts and then specific state-laws by which corporates are governed under these four categories.

Risk and compliance management is also significantly dependent on the sector, size, scale and nature of the business and the activities being carried out.

The woes of a large number of promoters from the ecommerce ecosystem are to do with streamlining systems to navigate legal. India has certain heavily regulated sectors and, like I mentioned earlier, an intricate web of corporate risk and compliance legislation that can result in prohibitive costs in the remedial phase. To tackle the web in the preventive or mitigative phase, start-ups end up lacking the arsenal due to sheer intimidation from legal. Promoters face sectoral risks in sectors which are heavily regulated, risks of heavy penalties and fines under company law or foreign exchange laws, if fund raise is not done in a compliant manner.

It is a myth that good legal advice comes at prohibitive costs. Promoters are quick to sign on the dotted line and approach lawyers with a tick the box approach. A lot of heartburn can be avoided if documents are entered into with proper legal advice and with due negotiations.

Investment contracts, large celebrity endorsement contracts and CXO contracts are some key areas where legal advice should be obtained. Online contracts is also emerging as an important area of concern.

When we talk of scope, arbitration is pretty much a default mechanism at this stage for adjudicating commercial disputes in India, especially given the fixation of timelines for closure of arbitration proceedings in India. The autonomy it allows the parties in dispute to pick a neutral and flexible forum for resolution is substantial. Lower courts being what they are in India, arbitration emerges as the only viable mode of dispute resolution in the Indian commercial context.

The arbitrability of disputes has evolved significantly in the last 10 years. The courts are essentially pro-arbitration when it comes to judging the arbitrability of subject matter and sending matters to arbitration quickly.

The Supreme Court’s ruling in the Vidya Drolia case has significantly clarified the position in respect of tenancy disputes, frauds and consumer disputes. It reflects upon the progressive approach of the court and aims to enable an efficient, autonomous and effective arbitration environment in India.

Law firms stand for ensuring that the law works for business and not against it. Whatever the scope of our mandate, the bottom line is to ensure a risk-free, conflict-free, compliant and prepared enterprise for our client, in a manner that does not intimidate the client or bog them down, regardless of the intricacy of the legal and regulatory web it takes to navigate to get to that end result. Lawyers need to dissect the business of law from the work.

This really involves meticulous, detail-oriented, sheer hard work on the facts, figures, dates and all other countless coordinates of each mandate, repetitively and even to a, so-called, “dull” routine rhythm – with consistent single-mindedness and unflinching resolve.

As a firm, multiply that effort into volumes, most of it against-the-clock given the compliance heavy ecosystem often riddled with uncertainties in a number of jurisdictions. So the same meticulous streamlining of mandate deliverables has to be extrapolated by the management of the firm to the junior most staff.

Further, the process of streamlining itself has to be more dynamic than ever now given the pace at which the new economy, tech-ecosystem, business climate as well as business development processes turn a new leaf.

Finally, but above all, we need to find a way to feel happy, positive and energized together as a team while chasing all of the aforesaid dreams. The competitive timelines and volumes at which a law firm works, this too is a real challenge. But we are happy to face it and evolve as we grow.

We always as a firm operated on the work from anywhere principle. We believed in it and inculcated this through document management processes to the last trainee. This helped us shut shop one day and continue from wherever we are operating.

The team has been regularly meeting online (at least once a day). We have been able to channel the time spent in travelling to and attending meetings in developing our internal knowledge banks further, streamline our processes, and work on integrating various tech to make the practice more cost-effective for our clients.

Right to Disclosure – Importance & Challenges in Criminal Justice System – By Manu Sharma

Personal liberty is the most cherished value of human life which thrives on the anvil of Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution of India (“the Constitution”). Once a person is named an accused, he faces the spectre of deprivation of his personal liberty and criminal trial. This threat is balanced by Constitutional safeguards which mandate adherence to the rule of law by the investigating agencies as well as the Court. Thus, any procedure which seeks to impinge on personal liberty must also be fair and reasonable. The right to life and personal liberty enshrined under article 21 of the Constitution, expanded in scope post Maneka Gandhi[1], yields the right to a fair trial and fair investigation. Fairness demands disclosure of anything relevant that may be of benefit to an accused. Further, the all-pervading principles of natural justice envisage the right to a fair hearing, which entails the right to a full defence. The right to a fair defence stems from full disclosure. Therefore, the right of an accused to disclosure emanates from this Constitutional philosophy embellished by the principles of natural justice and is codified under the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (“Code”).

Under English jurisprudence, the duty of disclosure is delineated in the Criminal Procedure and Investigations Act, 1996, which provides that the prosecutor must disclose to the accused any prosecution material which has not previously been disclosed to the accused and which might reasonably be considered capable of undermining the case for the prosecution against the accused or of assisting the case for the accused, except if such disclosure undermines public interest.[2] Fairness ordinarily requires that any material held by the prosecution which weakens its case or strengthens that of the defendant, if not relied on as part of its formal case against the defendant, should be disclosed to the defence.[3] The duty of disclosure under common law contemplates disclosure of anything which might assist the defence[4], even if such material was not to be used as evidence[5]. Under Indian criminal jurisprudence, which has borrowed liberally from common law, the duty of disclosure is embodied in sections 170(2), 173, 207 and 208 of the Code, which entail the forwarding of material to the Court and supply of copies thereof to the accused, subject to statutory exceptions.

II. Challenges in Enforcement

The right to disclosure is a salient feature of criminal justice, but its provenance and significance appear to be lost on the Indian criminal justice system. The woes of investigative bias and prosecutorial misconduct threaten to render this right otiose. That is not to say that the right of an accused to disclosure is indefeasible, as certain exceptions are cast in the Code itself, chief among them being public interest immunity under section 173(6). However, it is the mischief of the concept of ‘relied upon’ emerging from section 173(5) of the Code, which is wreaking havoc on the right to disclosure and is the central focus of this article. The rampant misuse of the words “on which the prosecution proposes to rely’ appearing in section 173(5) of the Code, to suppress material favourable to the accused or unfavourable to the prosecution in the garb of ‘un-relied documents’ has clogged criminal courts with avoidable litigation at the very nascent stage of supply of copies of documents under section 207 of the Code. The erosion of the right of an accused to disclosure through such subterfuge is exacerbated by the limited and restrictive validation of this right by criminal Courts. The dominant issues highlighted in the article, which stifle the right to disclosure are; tainted investigation, unscrupulous withholding of material beneficial to the accused by the prosecution, narrow interpretation by Courts of section 207 of the Code, and denial of the right to an accused to bring material on record in the pre-charge stage.

A. Tainted Investigation

Fair investigation is concomitant to the preservation of the right to fair disclosure and fair trial. It envisages collection of all material, irrespective of its inculpatory or exculpatory nature. However, investigation is often vitiated by the tendencies of overzealous investigating officers who detract from the ultimate objective of unearthing truth, with the aim of establishing guilt. Such proclivities result in collecting only incriminating material during investigation or ignoring the material favourable to the accused. This leads to suppression of material and scuttles the right of the accused to disclosure at the very inception. A tainted investigation leads to miscarriage of justice. Fortunately, the Courts are not bereft of power to supervise investigation and ensure that the right of an accused to fair disclosure remains protected. The Magistrate is conferred with wide amplitude of powers under section 156(3) of the Code to monitor investigation, and inheres all such powers which are incidental or implied to ensure proper investigation. This power can be exercised suo moto by the Magistrate at all stages of a criminal proceeding prior to the commencement of trial, so that an innocent person is not wrongly arraigned or a prima facie guilty person is not left out.[6]

B. Suppression of Material

Indian courts commonly witness that the prosecution is partisan while conducting the trial and is invariably driven by the lust for concluding in conviction. Such predisposition impels the prosecution to take advantage by selectively picking up words from the Code and excluding material favouring the accused or negating the prosecution case, with the aid of the concept of ‘relied upon’ within section 173(5) of the Code. However, the power of the prosecution to withhold material is not unbridled as the Constitutional mandate and statutory rights given to an accused place an implied obligation on the prosecution to make fair disclosure.[7] If the prosecution withholds vital evidence from the Court, it is liable to adverse inference flowing from section 114 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 (“Evidence Act). The prosecutor is expected to be guided by the Bar Council of India Rules which prescribe that an advocate appearing for the prosecution of a criminal trial shall so conduct the prosecution that it does not lead to conviction of the innocent. The suppression of material capable of establishment of the innocence of the accused shall be scrupulously avoided. [8]

C. Scope of S. 207

The scope of disclosure under section 207 has been the subject of fierce challenge in Indian Courts on account of the prosecution selectively supplying documents under the garb of ‘relied upon’ documents, to the prejudice of the defence of an accused. The earlier judicial trend had been to limit the supply of documents under section 207 of the Code to only those documents which were proposed to be relied upon by the prosecution. This view acquiesced the exclusion of documents which were seized during investigation, but not filed before the Court along with the charge sheet, rendering the right to disclosure a farce. This restrictive sweep fails to reconcile with the objective of a fair trial viz. discovery of truth. The scheme of the code discloses that Courts have been vested with extensive powers inter alia under sections 91, 156(3) and 311 to elicit the truth. Towards the same end, Courts are also empowered under Section 165 of the Evidence Act. Thus, the principle of harmonious construction warrants a more purposive interpretation of section 207 of the code. The Hon’ble Supreme Court expounded on the scope of Section 207 of the Code in the case of Manu Sharma[9] and held that documents submitted to the Magistrate under section 173(5) would deem to include the documents which have to be sent to the magistrate during the course of investigation under section 170(2). A document which has been obtained bona fide and has a bearing on the case of the prosecution should be disclosed to the accused and furnished to him to enable him to prepare a fair defence, particularly when non production or disclosure would affect administration of justice or prejudice the defence of the accused. It is not for the prosecution or the court to comprehend the prejudice that is likely to be caused to the accused. The perception of prejudice is for the accused to develop on reasonable basis.[10] Manu Sharma’s [supra] case has been relied upon in Sasikala [11] wherein it was held that the Court must concede a right to the accused to have access to the documents which were forwarded to the Court but not exhibited by the prosecution as they favoured the accused. These judgments seem more in consonance with the true spirit of fair disclosure and fair trial. However, despite such clear statements of law, courts are grappling with the judicial propensity of deviating from this expansive interpretation and regressing to the concept of relied upon. The same is evident from a recent pronouncement of the Delhi High Court where the ratios laid down in Manu Sharma & Sasikala [supra] were not followed by erroneously distinguishing from those cases.[12] Such “per incuriam” aberrations by High Court not only undermine the supremacy of the Apex Court, but also adversely impact the functioning of the district courts over which they exercise supervisory jurisdiction. Hopefully in future Judges shall be more circumspect and strictly follow the law declared by the Apex Court.

D. Pre-Charge Embargo

Another obstacle encountered in the enforcement of the right to disclosure is the earlier judicial approach to stave off production or consideration of any additional documents not filed alongwith the charge sheet at the pre-charge stage, as the right to file such material was available to the accused only upon the commencement of trial after framing of charge.[13] At the pre-charge stage, Court could not direct the prosecution to furnish copies of other documents[14] It was for the accused to do so during trial or at the time of entering his defence. However, the evolution of law has seen that at the stage of framing charge, Courts can rely upon the material which has been withheld by the prosecutor, even if such material is not part of the charge sheet, but is of such sterling quality demolishing the case of the prosecution.[15] Courts are not handicapped to consider relevant material at the stage of framing charge, which is not relied upon by the prosecution. It is no argument that the accused can ask for the documents withheld at the time of entering his defence.[16] The framing of charge is a serious matter in a criminal trial as it ordains an accused to face a long and arduous trial affecting his liberty. Therefore, the Court must have all relevant material before the stage of framing charge to ascertain if grave suspicion is made out or not. Full disclosure at the stage of section 207 of the code, which immediately precedes discharging or charging an accused, enables an accused to seek a discharge, if the documents, including those not relied upon by the prosecution, create an equally possible view in favour of the accused.[17] On the other hand, delaying the reception of documents postpones the vindication of the accused in an unworthy trial and causes injustice by subjecting him to the trauma of trial. There is no gainsaying that justice delayed is justice denied, therefore, such an approach ought not to receive judicial consent. A timely discharge also travels a long way in saving precious time of the judiciary, which is already overburdened by the burgeoning pendency of cases. Thus, delayed or piecemeal disclosure not only prejudices the defence of the accused, but also protracts the trial and occasions travesty of justice.

III. Duties of the stakeholders in criminal justice system

The foregoing analysis reveals that participation of the investigating agency, the prosecution and the Court is inextricably linked to the enforcement of the right to disclosure. The duties cast on these three stakeholders in the criminal justice system, are critical to the protection of this right. It is incumbent upon the investigating agencies to investigate cases fairly and to place on record all the material irrespective of its implication on the case of prosecution case. Investigation must be carried out with equal alacrity and fairness irrespective of status of accused or complainant.[18] An onerous duty is cast on the prosecution as an independent statutory officer, to conduct the trial with the objective of determination of truth and to ensure that material favourable to the defence is supplied to the accused. Ultimately, it is the overarching duty of the Court to ensure a fair trial towards the administration of justice for all parties. The principles of fair trial require the Court to strike a delicate balance between competing interests in a system of adversarial advocacy. Therefore, the court ought to exercise its power under section 156(3) of the Code to monitor investigation and ensure that all material, including that which enures to the benefit of the accused, is brought on record. Even at the stage of supply of copies of police report and documents under section 207 of the Code, it is the duty of the Court to give effect to the law laid down by the Hon’ble Supreme Court in Manu Sharma (supra) and Sasikala (supra), and ensure that all such material is supplied to the accused irrespective of whether it is “relied upon” by the prosecution or not.

IV. Alternate Remedy

The conundrum of supply of copies under section 207 of the code abounds criminal trials. Fairness is an evolving concept. There is no doubt that disclosure of all material which goes to establish the innocence of an accused is the sine qua non of a fair trial.[19] Effort is evidently underway to expand the concept in alignment with English jurisprudence. In the meanwhile, does the right of an accused to disclosure have another limb to stand on? Section 91 of the Code comes to the rescue of an accused, which confers wide discretionary powers on the Court, independent of section 173 of the Code, to summon the production of things or documents, relevant for the just adjudication of the case. In case the Court is of the opinion that the prosecution has withheld vital, relevant and admissible evidence from the Court, it can legitimately use its power under section 91 of the Code to discover the truth and to do complete justice to the accused.[20]

V. Conclusion

A society’s progress and advancement are judged on many parameters, an important one among them being the manner in which it administers criminal justice. Conversely, the ironic sacrilege of the core virtues of criminal jurisprudence in the temples of justice evinces social decadence. The Indian legislature of the twenty first century has given birth to several draconian statutes which place iron shackles on personal liberty, evoking widespread fear of police abuses and malicious prosecution. These statutes not only entail presumptions which reverse the burden of proof, but also include impediments to the grant of bail. Thus, a very heavy burden to dislodge the prosecution case is imposed on the accused, rendering the right to disclosure of paramount importance. It is the duty of the Court to keep vigil over this Constitutional and statutory right conferred on an accused by repudiating any procedure which prejudices his defence. Notable advancement has been made by the Apex Court in interpreting section 207 of the Code in conformity with the Constitutional mandate, including the right to disclosure. Strict adherence to the afore-noted principles will go a long way in ensuring real and substantial justice. Any departure will not only lead to judicial anarchy, but also further diminish the already dwindling faith of the public in the justice delivery system.

**

Advocate Manu Sharma has been practising at the bar for over sixteen years. He specialises in Criminal Defence. Some of the high profile cases he has represented are – the 2G scam case for former Union minister A Raja; the Religare/Fortis case for Malvinder Singh; Peter Mukerjee in the P Chidambaram/ INX Media case; Devas Multimedia in ISRO corruption act case; Om Prakash Chautala in PMLA case; Aditya Talwar in the aviation scam case; Dilip Ray, former Coal Minister in one of the coal scam cases; Suhaib Illyasi case.

**

Disclaimer: The views or opinions expressed are solely of the author.

[1] Maneka Gandhi and Another v. Union of India, (1978) 1 SCC 248

[2] S. 3 of the Criminal Procedure and Investigations Act, 1996

[3] R v. H and R v. C, 2004 (1) ALL ER 1269

[4] R v. Ward (Judith), (1993) 1 WLR 619 : (1993) 2 ALL ER 577 (CA)

[5] R v. Preston, (1994) 2 AC 130 : (1993) 3 WLR 891 : (1993) 4 ALL ER 638 (HL), R v. Stinchcome,

(1991), 68 C.C.C. (3d) 1 (S.C.C.)

[6] Vinubhai Haribhai Malaviya and Others v. State of Gujarat and Another, 2019 SCC Online SC 1346

[7] Sidhartha Vashishth alias Manu Sharma v. State (NCT of Delhi), (2010) 6 SCC 1

[8] R. 16, part II, Ch. VI of the Bar Council of India Rules

[9] Manu Sharma, (2010) 6 SCC 1

[10] V.K. Sasikala v. State, (2012) 9 SCC 771 : AIR 2013 SC 613

[11] Sasikala, (2012) 9 SCC 771 : AIR 2013 SC 613

[12] Sala Gupta and Another v. Directorate of Enforcement, (2019) 262 DLT 661

[13] State of Orissa v. Debendra Nath Padhi¸(2005) 1 SCC 568

[14] Dharambir v. Central Bureau of Investigation, ILR (2008) 2 Del 842 : (2008) 148 DLT 289

[15] Nitya Dharmananda alias K. Lenin and Another v. Gopal Sheelum Reddy, (2018) 2 SCC 93

[16] Neelesh Jain v. State of Rajasthan, 2006 Cri LJ 2151

[17] Dilwar Balu Kurane v. State of Maharashtra, (2002) 2 SCC 135, Yogesh alias Sachin Jagdish Joshi v. State of Maharashtra, (2008) 10 SCC 394

[18] Karan Singh v. State of Haryana, (2013) 12 SCC 529

[19] Kanwar Jagat Singh v. Directorate of Enforcement & Anr, (2007) 142 DLT 49

[20] Neelesh, 2006 Cri LJ 2151

Disclaimer: The views or opinions expressed are solely of the author.

Validity & Existence of an Arbitration Clause in an Unstamped Agreement

By Kunal Kumar

January 8, 2024

In a recent ruling, a seven-judge bench of the Supreme Court of India in its judgment in re: Interplay between arbitration agreements under the Arbitration & Conciliation Act 1996 and the Indian Stamp Act 1899, overruled the constitutional bench decision of the Supreme Court of India in N. N. Mercantile Private Limited v. Indo Unique Flame Ltd. & Ors. and has settled the issue concerning the validity and existence of an arbitration clause in an unstamped agreement. (‘N. N. Global Mercantile (P) Ltd. v. Indo Unique Flame Ltd. – III’)

Background to N. N. Global Mercantile (P) Ltd. v. Indo Unique Flame Ltd. – III

One of the first instances concerning the issue of the validity of an unstamped agreement arose in the case of SMS Tea Estate Pvt. Ltd. v. Chandmari Tea Company Pvt. Ltd. In this case, the Hon’ble Apex Court held that if an instrument/document lacks proper stamping, the exercising Court must preclude itself from acting upon it, including the arbitration clause. It further emphasized that it is imperative for the Court to impound such documents/instruments and must accordingly adhere to the prescribed procedure outlined in the Indian Stamp Act 1899.

With the introduction of the 2015 Amendment, Section 11(6A) was inserted in the Arbitration & Conciliation Act 1996 (A&C Act) which stated whilst appointing an arbitrator under the A&C Act, the Court must confine itself to the examination of the existence of an arbitration agreement.

In the case of M/s Duro Felguera S.A. v. M/s Gangavaram Port Limited, the Supreme Court of India made a noteworthy observation, affirming that the legislative intent behind the 2015 Amendment to the A&C Act was necessitated to minimise the Court's involvement during the stage of appointing an arbitrator and that the purpose embodied in Section 11(6A) of A&C Act, deserves due acknowledgement & respect.

In the case of Garware Wall Ropes Ltd. v. Cosatal Marine Constructions & Engineering Ltd., a divisional bench of the Apex Court reaffirmed its previous decision held in SMS Tea Estates (supra) and concluded that the inclusion of an arbitration clause in a contract assumes significance, emphasizing that the agreement transforms into a contract only when it holds legal enforceability. The Apex Court observed that an agreement fails to attain the status of a contract and would not be legally enforceable unless it bears the requisite stamp as mandated under the Indian Stamp Act 1899. Accordingly, the Court concluded that Section 11(6A) read in conjunction with Section 7(2) of the A&C Act and Section 2(h) of the Indian Contract Act 1872, clarified that the existence of an arbitration clause within an agreement is contingent on its legal enforceability and that the 2015 Amendment of the A&C Act to Section 11(6A) had not altered the principles laid out in SMS Tea Estates (supra).

Brief Factual Matrix – N. N. Global Mercantile (P) Ltd. v. Indo Unique Flame Ltd.

Indo Unique Flame Ltd. (‘Indo Unique’) was awarded a contract for a coal beneficiation/washing project with Karnataka Power Corporation Ltd. (‘KPCL’). In the course of the project, Indo Unique entered into a subcontract in the form of a Work Order with N.N. Global Mercantile Pvt. Ltd. (‘N.N. Global’) for coal transportation, coal handling and loading. Subsequently, certain disputes arose with KPCL, leading to KPCL invoking Bank Guarantees of Indo Unique under the main contract, after which Indo Unique invoked the Bank Guarantee of N. N. Global as supplied under the Work Order.

Top of FormS

Subsequently, N.N. Global initiated legal proceedings against the cashing of the Bank Guarantee in a Commercial Court. In response thereto, Indo Unique moved an application under Section 8 of the A&C Act, requesting that the Parties to the dispute be referred for arbitration. The Commercial Court dismissed the Section 8 application, citing the unstamped status of the Work Order as one of the grounds. Dissatisfied with the Commercial Court's decision on 18 January 2018, Indo Unique filed a Writ Petition before the High Court of Bombay seeking that the Order passed by the Commercial Court be quashed or set aside. The Hon’ble Bombay High Court on 30 September 2020 allowed the Writ Petition filed by Indo Unique, aggrieved by which, N.N. Global filed a Special Leave Petition before the Supreme Court of India.

N. N. Global Mercantile Pvt. Ltd. v. Indo Unique Flame Ltd. – I

The issue in the matter of M/s N.N. Global Mercantile Pvt. Ltd. v. M/s Indo Unqiue Flame Ltd. & Ors. came up before a three-bench of the Supreme Court of India i.e. in a situation when an underlying contract is not stamped or is insufficiently stamped, as required under the Indian Stamp Act 1899, would that also render the arbitration clause as non-existent and/or unenforceable (‘N.N. Global Mercantile Pvt. Ltd. v. Indo Flame Ltd. – I’).

The Hon’ble Supreme Court of India whilst emphasizing the 'Doctrine of Separability' of an arbitration agreement held that the non-payment of stamp duty on the commercial contract would not invalidate, vitiate, or render the arbitration clause as unenforceable, because the arbitration agreement is considered an independent contract from the main contract, and the existence and/or validity of an arbitration clause is not conditional on the stamping of a contract. The Hon’ble Supreme Court further held that deficiency in stamp duty of a contract is a curable defect and that the deficiency in stamp duty on the work order, would not affect the validity and/or enforceability of the arbitration clause, thus applying the Doctrine of Separability. The arbitration agreement remains valid and enforceable even if the main contract, within which it is embedded, is not admissible in evidence owing to lack of stamping.

The Hon’ble Apex Court, however, considered it appropriate to refer the issue i.e. whether unstamped instrument/document, would also render an arbitration clause as non-existent, unenforceable, to a constitutional bench of five-bench of the Supreme Court.

N. N. Global Mercantile (P) Ltd. v. Indo Unique Flame Ltd. – II

On 25 April 2023, a five-judge bench of the Hon’ble Supreme Court of India in the matter of N. N. Mercantile Private Limited v. Indo Unique Flame Ltd. & Ors. held that (1) An unstamped instrument containing an arbitration agreement cannot be said to be a contract which is enforceable in law within the meaning of Section 2(h) of the Indian Contract Act 1872 and would be void under Section 2(g) of the Indian Contract Act 1872, (2) an unstamped instrument which is not a contract nor enforceable cannot be acted upon unless it is duly stamped, and would not otherwise exist in the eyes of the law, (3) the certified copy of the arbitration agreement produced before a Court, must clearly indicate the stamp duty paid on the instrument, (4) the Court exercising its power in appointing an arbitration under Section 11 of the A&C Act, is required to act in terms of Section 33 and Section 35 of the Indian Stamp Act 1899 (N. N. Global Mercantile (P) Ltd. v. Indo Unique Flame Ltd. – II).

N. N. Global Mercantile (P) Ltd. v. Indo Unique Flame Ltd. – III

A seven-judge bench of the Supreme Court of India on 13 December 2023 in its recent judgment in re: Interplay between arbitration agreements under the Arbitration & Conciliation Act 1996 and the Indian Stamp Act 1899, (1) Agreements lacking proper stamping or inadequately stamped are deemed inadmissible as evidence under Section 35 of the Stamp Act. However, such agreements are not automatically rendered void or unenforceable ab initio; (2) non-stamping or insufficient stamping of a contract is a curable defect, (2) the issue of stamping is not subject to determination under Sections 8 or 11 of the A&C Act by a Court. The concerned Court is only required to assess the prima facie existence of the arbitration agreement, separate from concerns related to stamping, and (3) any objections pertaining to the stamping of the agreement would fall within the jurisdiction of the arbitral tribunal. Accordingly, the decision in N. N. Global Mercantile (P) Ltd. v. Indo Unique Flame Ltd. – II and SMS Tea (supra) was overruled, by the seven-judge bench of the Supreme Court of India.

Kunal is a qualified lawyer with more than nine years of experience and has completed his LL.M. in Dispute Resolution (specialisation in International Commercial Arbitration) from Straus Institute for Dispute Resolution, Pepperdine University, California.

Kunal currently has his own independent practice and specializes in commercial/construction arbitration as well as civil litigation. He has handled several matters relating to Civil Law and arbitrations (both domestic and international) and has appeared before the Supreme Court of India, High Court of Delhi, District Courts of Delhi and various other tribunals.

No Safe Harbour For Google On Trademark Infringement

By Mayank Grover & Pratibha Vyas

October 9, 2023

Innovation, patience, dedication and uniqueness culminate in establishing a distinct identity. A trademark aids in identifying the source and quality, shaping perceptions about the identity's essence. When values accompany a product or service's trademark, safeguarding against misuse and infringement becomes crucial. A recent pronouncement of a Division Bench of the Delhi High Court dated August 10, 2023 in Google LLC v. DRS Logistics (P) Ltd. & Ors. and Google India Private Limited v. DRS Logistics (P) Ltd. & Ors. directed that Google’s use of trademarks as keywords for its Google Ads Programme does amount to ‘use’ in advertising under the Trademarks Act and the benefit of safe harbour would not be available to Google if such keywords infringe on the concerned trademark.

Factual Background

Google LLC manages and operates the Google Search Engine and Ads Programme, while, Google India Private Limited is a subsidiary of Google that has been appointed as a non-exclusive reseller of the Ads Programme in India. The Respondents, DRS Logistics and Agarwal Packers and Movers Pvt. Ltd. are leading packaging, moving and logistics service providers in India.

On 22.12.2011, DRS filed a suit against Google and Just Dial Ltd. under provisions of the Trademarks Act, 1999 (‘TM Act’) inter alia seeking a permanent injunction against Google from permitting third parties from infringing, passing off etc. the relevant trademarks of DRS. The core of the dispute revolved around Google’s Ads Programme. DRS claimed that its trade name 'AGARWAL PACKERS AND MOVERS' is widely recognized and a 'well-known' trademark. Use of DRS’s trademark as a keyword diverts internet traffic from its website to that of its competitors and they were entitled to seek restraint against Google for permitting third parties who are not authorized to use the said trademark. DRS further argued that Google benefits from these trademark infringements. This practice involved charging a higher amount for displaying these ads, constituting an infringement of their trademarks. Whereas, Google contended that the use of the keyword in the Ads Programme does not amount to ‘use’ under the TM Act notwithstanding that the keyword is/or similar to a trademark. Thus, the use of a term as a keyword cannot be construed as an infringement of a trademark under the TM Act, and being an intermediary, it claimed a safe harbour under Section 79 of the Information Technology Act, 2000. (‘IT Act’).

In essence, the dispute between the parties was rooted in DRS’s grievance concerning the Ads Programme. The Learned Single Judge vide judgment dated 30.10.2021interpreted relevant provisions of the TM Act and drew on multiple legal precedents to arrive at the decision that DRS can seek protection of its trademarks which were registered under Section 28 of the TM Act and issued directions to investigate complaints alleging the use of trademark and/or to ascertain whether a sponsored result has an effect of infringing a trademark or passing off.

Being aggrieved, Google LLC and Google Pvt. Ltd. filed appeals before the Division Bench. Google LLC argued that the Single Judge’s findings were erroneous and the directions issued were liable to be set aside. Google India claimed that it doesn’t control and operate the Search Engine and the Ads Programme making it unable to comply with the directions passed in the impugned judgment.

Analysis & Decision of Court

The Division Bench found Single Judge’s rationale for assessing trademark infringement through keywords and meta-tags valid. Meta-tags are a list of words/code in a website, not readily visible to the naked eye. It serves as a tool for indexing the website by a search engine. If a trademark of a third party is used as a meta-tag, the same would serve as identifying the website as relevant to the search query that includes the trademark as a search term. The use of keywords in the Ads Programme also serves similar purpose. The Division Bench was unable to accept that using a trademark as a keyword, even if not visible, would not be considered trademark use under the TM Act.

Google placed heavy reliance on the decisions rendered by Courts across jurisdictions of United Kingdom, United States of America, European Union, Australia, New Zealand, Russia, South Africa, Canada, Spain, Italy, Japan and China; in the cases of Google France SARL and Google Inc. v. Louis Vitton SA & Ors.[1], Interflora Inc. v. Marks & Spencer Plc.[2], and L’Oreal SA v. eBay International AG[3] in support of the contention that the use of trade marks is by the advertiser and not by Google. However, the Division Bench rejected Google’s passive role; highlighting its active involvement in recommending and promoting trademark keywords for higher clicks in its Ads Programme. Division Bench referred to a few judicial decisions rendered in the United States of America that captured the essence of the controversy for perspective, concluding that Google actively promotes and encourages trademarks associated with major goods and services, rather than having a passive role.

It was held that the contention that the use of trademarks as keywords, per se constitutes an infringement of the trademark is unmerited; the assumption that an internet user is merely searching the address of the proprietor of the trademark when he feeds in a search query that may contain a trademark, is erroneous.

The Doctrine of 'Initial Interest Confusion' addresses trademark infringement based on pre-purchase confusion. The doctrine is applied when meta-tags, keywords, or domain names cause initial confusion similar to a registered trademark. If users are misled to access unrelated websites, trademark use in internet advertising may be actionable and reliance was placed on US precedents. Referring to Section 29 of the TM Act, it was directed that Section 29 does not specify the duration for which the confusion lasts but, even if the confusion is for a short duration and an internet user is able to recover from the same, the trade mark would be infringed and would offend Section 29(2) of the TM Act.

It was held that the Ads Programme is a platform for displaying advertisements. Google, being an architect and operator of its own programme makes it an active participant in the use of trademarks and determining the advertisements displayed on search pages. Their use of proprietary software makes them utilize trademarks and control the distribution of information related to potentially infringing links, ultimately leading to revenue maximization. Hence, a substantial link exists between Google LLC and Google India, rendering it impossible for Google India to deny its role in operating the Ads Programme. It was further held that Google sells trademarks as keywords to advertisers and encourages users to use trademarks as keywords for ads. It is contradictory for Google to encourage trademark use while claiming data belongs to third parties for exemption. After 2004, Google changed policies to boost revenue and subsequently, introduced a tool that searches effective terms, including trademarks. Google's active involvement in its advertising business and online nature does not necessarily qualify it for benefits under Section 79 of the IT Act. The Division Bench agreed with the view of the Single Judge that Google would not be eligible for protection of safe harbour under Section 79(1) of the IT Act, if its alleged activities infringe trademarks.

Conclusion

This is a seminal decision governing (and rather, restricting) the operations of intermediaries and redefining the jurisprudence of safe harbour under the IT Act. The decision is well-reasoned and establishes a significant precedent for safeguarding trademarks by uniquely holding Google accountable under its Ads Programme. The same will prevent usage of tradenames as a third-party trademark in keyword search or metatags by advertisers on Google’s search engine. While keywords and meta-tags have different levels of visibility, their purpose is similar i.e. advertising and attracting internet traffic. The use of trademarks as meta-tags by a person who is neither a proprietor of the trademark nor permitted to use the same leads to confusion amongst public at large due to the automated processes of search engines and consequently, constitutes trademark infringement.

About the Authors: Mayank Grover is a Partner and Pratibha Vyas is an Associate at Seraphic Advisors, Advocates & Solicitors

[1] C-236/08 to C-238/08 (2010) [2011] All ER (EC) 41

[2] [2014] EWCA Civ 1403

[3] 2C- 324/09 (2010)

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to stay up to date on our product, events featured blog, special offer and all of the exciting things that take place here at Legitquest.