Yaksha Prashnas - The Vexed Questions of Caste and Sword Marriage: What the Madras High Court Said in the Judgment of 1924

By Jayant Mohan

In the case of Maharaja of Kolhapur Vs S Sunderam Ayyar, the following issues arose and were decided:

a) What is the status of the Raja's offspring by sword-wife mothers in this family? Are they legitimate or illegitimate? Are sword-wives a species of inferior wives or kind a of super concubines?

b) Is the family, to which the late Raja of Tanjore belonged, a family of Kshatriyas or Sudras?

1. ‘Yaksha Prashnas’ or the vexed and unanswerable questions as stated above arose for the Indian Judges in pre-independence India with the interplay of the Indian Princes and Rulers Religious Beliefs, Customs with History and Legal System regarding Succession and Marriage Laws of the Maharajas and Princes. It is most interesting as to how the said issues were dealt with and judgment rendered by Secular Court of Law regarding Questions of Religion and History .

‘Yaksha’ in Vedic Mythology denotes ‘the benevolent spirit’. In Mahabharata the story of Pandavas at the end of their 12 year exile occurs known as ‘Yaksha Prashna’ which is a question-answer dialogue between Yudhishthira and the ‘Yaksha’ or ‘Noble Spirit’.

The story goes that the Pandavas were very thirsty in the middle of wild forests. Nakul, Sahdev, Arjun and Bhima went in search of drinking water. They reached a beautiful lake, each one after the other, and died after drinking water from the lake. They had ignored the warnings of the White Crane guarding the lake to first answer the questions and only then drink water.

Finally, when Yudhishthir reached the beautiful lake looking for his brothers, the White Crane reiterated the warning that anyone drinking water from the lake must answer his questions beforehand otherwise they will die. Yudhishthira agreed to answer the questions of the White Crane.

Thereafter, the Crane turned into a ‘Yaksha’ or ‘Noble Spirit’ and started asking 125 questions on God, Religion, Philosophy and Dharma which Yudhishthira answered.

The Answers of Yudhishthira made the ‘Yaksha’ very happy and he revived all the Pandava brothers back to life.

Then, the Yaksha revealed his true form of Yama-Dharma or ‘God of Death’ being the father of Yudhishthira and blessed him that the Pandavas will be protected because the eldest Pandava follows the path of Dharma (righteousness) and deserves the title of ‘Dharma Raj’ or ‘Most Pious One’.

Similarly, ‘Yaksha Prashnas’ arose for adjudication before the Courts in colonial pre-independence India between Queens Proclamation in 1858 and 1947 when India became independent.

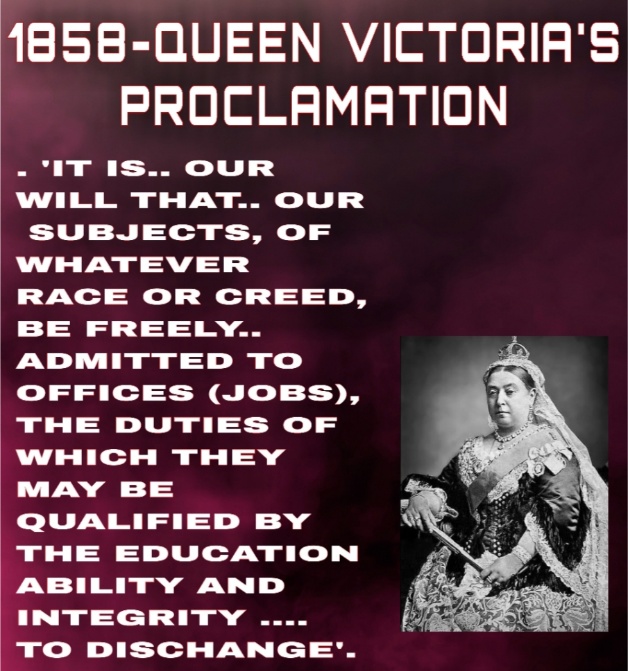

QUEEN VICTORIA’S PROCLAMATION OF 1858 AND RESPECT FOR LOCAL CUSTOMS

In the aftermath of the 1857 rebellion, the British Government passed the Government of India Act, taking over direct control of the administration in India from the East India Company.

Queen Victoria’s Proclamation held on 1st November, 1858 at Allahabad granted to ‘the natives of our Indian territories’ the same rights as ‘all our other subjects’ and, among other things, promised to support religious toleration, to recognize the ‘customs of India’, to end racial discrimination and to ensure that ‘all shall alike enjoy the equal impartial protection of the law’.

This respect for ‘Customs of India’ was a significant shift from the previous

policy of the doctrine of lapse being followed by Lord Dalhousie under the East

India Company Rule to annex the kingdoms of Indian Princes and Rulers who

did not have a proper male lineal heir to the Ruler.

Under the Policy the British annexed the state of Satara, Jaitpur, Sambhalpur, Nagpur and most importantly Awadh (Oudh) between 1849 to 1856 which was one of the main causes of the Rebellion of 1857 against the Company Rule resulting in widespread violence and deaths of English persons, which undermined British authority.

Therefore, under the direct rule of Queen Victoria, the British Officials and the Administrators were very careful in dealing with the succession rights of Indian Rulers and Princes and the matters of succession were inevitably settled through the intervention of Courts.

The interplay of the Indian Princes and Rulers’ religious beliefs and customs with the orders and proclamations issued by British administrators resulted in complicated legal status of the heirs and inheritance was always heavily contested in the Courts of Law.

The Law Courts were called upon to decide such complex historical, social and mythological questions like what is the ‘Caste’ or ‘Gotra’ of Rajas or ‘Validity of Sword Marriages’ etc.

THE CASE WHERE THE ISSUE WAS THE CASTE OF SHIVAJI THE GREAT

At the crossroads of history, law and religion was one such succession battle between various claimants to the private properties of the Raja of Tanjore which came to be decided by the Madras High Court in the case of Maharaja of Kolhapur Vs S Sunderam Ayyar decided on January 21,1924.

The decision was rendered on 21st January, 1924 by the Madras High Court regarding succession of the magnificent Tanjore Fort and personal properties of the last Maharaja of Tanjore who had passed away in 1855.

The said first appeal arose from the decision of Subordinate Judge-Tanjore dated 2nd July, 1918 where amongst the 72 issues decided by the Judge were the two questions mentioned in the beginning which stand out for their unique complexity;

Sword Marriage’ was a prevalent form of marriage amongst the ruling Maharajas and Princes of India where many women were married to the sword or the dagger of the Raja, sword representing the Raja or the King. Such form of marriage was prevalent amongst the Kshatriyas because the sword or dagger was representative of the Kshatriyas whose profession was of arms. There was no giving away of the bride to the groom, treated to be an essential feature of marriage.

‘Sword Marriages’ were treated by the Pandits to be ‘Gandharva Marriage’ (a marriage importing amorous connection found on reciprocal desire) form, being that there was no giving away of the bride.

Recently, a popular Hindi movie ‘Bajirao Mastani’ on the romance between Bajirao Peshwa (1700-1740), the Maratha King, with Mastani (1699-1740), daughter of Maharaja Chhatrasaal of Bundelkhand, has been portrayed on screen. Mastani was the second wife of Peshwa. Many historians are of the view that Mastani was married to the sword of Bajirao Peshwa in Bundelkhand and later on was brought to Pune, the seat of Peshwa, to cohabit with him as his second wife.

The Bench which decided the Appeal before the Madras High Court comprised of the officiating Chief Justice Charles Gordon Spencer and Justice Kumaraswami Sastri. The most fascinating aspect of the process is how a British Judge (the officiating Chief Justice) decided the complicated issues pertaining to Indian history, mythology and religious beliefs and customs. Remarkable erudition, research and scholarship is evident from the reading of the decision. Justice Kumaraswami Sastri agreed with the opinion of Justice Spencer but wrote a separate judgment detailing separate reasons and supporting the conclusions of officiating Chief Justice.

The Judgment of Charles Gordon Spencer starts with the following line

“In A.D. 1674 during the reign of the great Mogul Emperor Aurangzeb, Ekoji alias Venkaji took Tanjore from its Nayak Rulers without firing a shot.

….In 1677 the forces of Ekoji and those of his half brother Sivaji came into conflict but by a compromise the former was allowed to retain Tanjore. In 1680 Sivaji got Tanjore and other territories ceded to him by the Bijapur Government, but in the same year Sivaji died and Ekoji retained his-hold on Tanjore.”

With the aforesaid Words, the Judgment proceeds to narrate the factual background which was the subject matter of the case being the ‘suit property’ namely the magnificent Tanjore Fort and Lands which were the personal properties of the Maharaja of Tanjore.

FACTUAL BACKGROUND OF THE CASE

On one side was the successors of Sivaji the great - the founder of the Maratha Empire in Deccan India represented through Maharaja of Kolhapur claiming the suit property. On the other side were the Successors of Ekoji (half brother of Shivaji) and Maharaja of Tanjore claiming rights by succession in the personal property of Ekoji. The successor of Ekoji being Last Ruler of Tanjore (Sivaji) passed away in 1855.

Since the last Maharaja of Tanjore did not have a male heir, he married 17 women in one day through ‘Sword Marriage’ in 1851 in a desperate attempt to get male heirs.

On October 29th, 1855, he left 15 Ranis, two legitimate daughters, a mother, 60 women living in a seraglio called the Mangala Vilas, of whom 40 aspired to be called sword wives in distinction to the dancing girls who were ordinary concubines, and 17 natural children begotten by the Raja through sword wives, six of these children being males

The British Government declared the Raja of the Tanjore State to have lapsed and vested with the Government of India as he did not leave behind a male heir.

As far as the personal properties of the Raja of Tanjore, namely the Tanjore Fort and the lands and other properties of the Maharaja of Tanjore were concerned, the Government of Madras issued a Government Order in 1862 handing over the Estate to be managed by the Widow of Raja of Tanjore namely Kamakshi Bai for management and control. The Government Order also mandated that on the death of the last surviving widow the Property will devolve upon the daughter of the Raja or failing her the next legal heir of the Raja.

Kamakshi Bai, the widow of the last Raja of Tanjore, died in 1912.

The receiver on July 8th, 1912, instituted this interpleader suit to decide who was entitled to take the estate making the adopted son's sons, the daughter's adopted grandchild, the sons and grandsons of the Raja by his sword wives, distant agnates including the Maharaja of Kolhapur, the descendants of the last ruler of Satara and of the Patel of Jinti, and remote bandhus, in fact all possible claimants, parties to the suit. The trial commenced on July 2nd, 1917 before the Subordinate Judge, Tanjore and judgment was pronounced on July 1st, 1918, after voluminous evidence had been recorded and innumerable exhibits admitted.

How the issue of validity of Sword Marriages and rights of the Children born out of such marriages was decided

While deciding on the vexed issue of validity of sword marriage and legitimacy of children born out of sword marriages, the court considered the voluminous evidence as well as primary sources of information such as historical accounts, treatises by scholars and literary and official accounts regarding practices and customs of ‘Sword Marriages amongst the Ruling classes’ was taken into account;

In the aforesaid background the issue of Caste of Ruler of Tanjore from Ekoji being half brother of Shivaji the Great came to be decided by the High Court. The Court relied upon evidence and materials to conclude ‘Sword Marriages’ were in fact a valid form of marriage but only amongst the Kshatriyas.

The High Court disagreed with the finding that Sword Wives was a valid form of marriage in the family of Raja of Tanjore but the status of Sword Wives was that of inferior wives. Therefore, the children born out Sword Marriages are ‘illegitimate’ and only entitled to be given shares reserved for illegitimate sons as per Hindu law and held that Sword Marriages were a valid form of marriage amongst Kshatriyas.

The High Court disagreed with the approach of the Subordinate Judge and held that there cannot be a half-way house regarding legitimacy and illegitimacy. Therefore, it is necessary to find whether the Sword Wives were regularly married or they were concubines whose offspring are illegitimate.

How the Issue of Caste of Shivaji the Great became an issue to be decided by the High Court

The validity of Sword Marriages and the right to inherit for offspring born out of such Sword Marriages will depend on the finding whether the fact that Raja of Tanjore belongs to Kshatriya caste or not since the first Raja of Tanjore i.e. Ekoji was the half-brother of Shivaji and both had common ancestors. Therefore, the issue of caste of Shivaji the Great arose and had to be decided upon.

Historical accounts record that Shivaji the great was the most Powerful Maratha Ruler in the Deccan. He was anointed/initiated by Gaga Bhat, a Brahmin from Benaras, at the age of 47 years in a regal ceremony for coronation of Shivaji the Great held at 6th June, 1674 at Raigad.

While determining the caste issue, three historical facts had to be probed which had arisen from the material on record:

1. Gaga Bhat, a Brahmin from Benaras did the Upananyanam or thread ceremony thereby raising Shivaji to the rank of Kshatriya and conferring on him the title ’Chhatrpati” or “Chief, Head King of Kshatriyas”.

2. Origins of the Mahratta Clan who traced their lineage to the Rajput Rulers from Udaipur (Ranas of Mewar) and the Mahrathas’ claim that they descend from the Ranas of Mewar being the first 96 families who had initially migrated from Udaipur and settled in Deccan.

3. In performing the Upanayana Sanskar of Shivaji there was considerable opposition from other Brahmins and Pandits of the time who claimed that in Kaliyuga there are no kshatriyas because they were extinguished by the Sage Parshuram.

The Veracity of the aforesaid facts had to be ascertained from the proof and evidence on record which the court proceeded with in the following manner;

Upanayanam (Thread marriage) of Shivaji the Great

The Judgment notes from the Satara Gazetter and Kolhapur Gazeteer prepared by the Administrators recording the facts and history of the District and people regarding the Thread ceremony or Upanayanam of Shivaji the Great for which a Pandit from Benaras had been called and he raised Shivaji to the rank of Kshatriya after the Upanayana Ceremony.

“It is a matter of history that Sivaji paid four lakhs of rupees to Gaga Bhat, a Brahmin of Benares, in order to have his upanayanam (thread marriage) performed when he was 47 years of age, and to be raised to the rank of a Kshatriya at the time of his coronation. In the Kolhapur Gazetteer, page 72, it is stated that the descendants of Sivaji. claim to belong to the Kshatriya caste and say that their ceremonies are the same as those of Brahmins.”

The brilliance of the Judge is evident from the way this vexed issue of “Gaga Bhat – A Brahmin from Benaras having been prevailed upon to perform the Upanayam sanskar of Shivaji the Great Maratha Ruler has been dealt with. The Judge considers this one event has been described by three scholars from three different viewpoints in the judgment as follows;

1. As per J Sarkar’s "Shivaji," pages 240-246, that Shivaji underwent a public purification for having omitted to observe Kshatriya rites for long. Thereafter a meeting of Brahmins was held who opposed Gaga Bhat to initiate Shivaji as they asserted that in Kaliyuga there was no true Kshatriya as Sage Parashuram had extinguished them. Gaga Bhat then proceeded to initiate Shivaji in modified form with Vedic mantras overcoming opposition.

2. Mr. Ben in his recent book called Siva Chhatrapati, published while these appeals were awaiting a hearing, that the argument that there were many Sudra kings without any knowledge of Kshatriya rites, though urged for the space of a year and a half, had no effect on Gaga Bhat but that he was finally prevailed upon to crown Sivaji by the plea that he was kind to his subjects, and maintained the true religion (pages 241-242).

3. Subasat's Bakar, page 114, that Gaga Bhat was satisfied by means of an emissary sent to Rajputana that Sivaji's ancestors came from Kshatriya families and that he was a Suddha (proper) Kshatriya is correct.

Despite the three versions of the same event as described by scholars having been noted by the Court it was found unnecessary to give an opinion on the issue of caste of Shivaji on this much vexed question in the following words:

“assuming that Sivaji and his descendants are Kshatriyas, it does not follow that Ekoji, his half-brother, who did not go through the ceremonies of purification and coronation, as Sivaji did, and his descendants are anything more than Sudras”

Therefore, the Court refrained from giving a finding regarding the Caste of Shivaji the Great – Founder of the Maratha Empire.

ORIGINS OF ANCESTRY OF THE MARATHAS BEING 96 FAMILIES DESCENDED FROM THE RANAS OF UDAIPUR

The Court noted the historical claim that Marathas had Migrated from Udaipur and were the Descendants of the Rana of Udaipur from Mewar State in Rajputana :

“The highest class of Mahrattas is supposed to consist of ninety-six families, who profess to be of Rajput descent and to represent the Kshatriyas of the traditional system.”

This theory of the origins of Marathas was considered from the stand point of various historical and literary accounts. Also, voluminous evidence was led before the Subordinate Judge who had rejected the theory of origin of Marathas from Rajputana. The Court was of the view that there is no basis to prove that the descendants of Ranas of Mewar had come to so much distance to the south and found an empire and following finding regarding origins of the Marathas from the Ranas of Mewar regarding ancestors of Rulers of Mahratta Empire and Tanjore State

“On the whole it must be said that historically, genealogically, geographically, socially and ceremonially, the claim of this family to be classed as Kshatriyas has failed and the lower Court's finding on this point must be confirmed.”

In the aforesaid manner the Court affirmed the finding of the Subordinate Judge Tanjore that the Maharaja of Tanjore was not Kshatriya by caste and the claim of successors to inherit the property from Sword Marriage was rejected.

WHETHER NO KSHATRIYAS EXIST IN KALIYUGA BECAUSE SAGE PARSHURAM HAD DESTROYED THEM

In opposition to anointing Shivaji as a Kshatriya, some Brahmins and objected that in Kaliyuga no Kshatriyas exist because Parshuram a Sage had destroyed all Kshatriyas. The said theory is rejected by the Court and concludes that Kshatriyas continue to exist relying upon the decision of Privy Council in Ma Yait v. Maung Chit Maung A.I.R. 1922 P.C. 197 that concept of Caste is dynamic and notes the evolution of Hindu castes by occupation, migration and intermarriage, and new castes have been evolved among the descendants of Hindus are to be considered as having retained in the Hindu religion, and observes that the formation of new castes is a process which is constantly going on.

CONCLUSIONS AND LESSONS IN JUDICIAL WISDOM

In my opinion the remarkable decision shows judicial statesmanship, wisdom and scholarship wherein the Hon’ble Judges had considered the complicated issues of religion and history being ‘Yaksha Prashnas’.

The Court adjudicated with wisdom, logic and legal reasoning on the sensitive issue of ‘caste’ of one of the icons of India - Shivaji who was the founder of the Maratha Empire.

The Judges showed considerable respect and sensitivity of the issue of caste of Shivaji and the far reaching implications it may have on the descendants of Shivaji the Great . Therefore, the Court in its wisdom refrained from recording a finding on whether the caste of Shivaji was Kshatriya or not because the same may cause prejudice to the descendants of Shivaji, i.e. Maharaja of Kolhapur and Satara branches of the family of Shivaji who were parties in the case .

The Approach of the Court as observed from the decision is a shining example for Judges and Lawyers who are involved in deciding upon emotionally charged issues of life, religion and law with poise, dispassionate analysis based on logic and reasoning and most importantly keeping aware of the guiding light the golden words inscribed on the National Emblem of India - The Ashok Chakra with Three Lions namely:

Satyamev Jayate- Truth Always Prevails

_________________________________________________________

Jayant Mohan is an Advocate-on-Record in the Supreme Court. Practising since 2005, he has varied experience before the Apex Court in matters related to Constitutional and Criminal law, more particularly PILs related to the Environment, Mining Laws and Criminal Cases. He represents the State of Jharkhand before the Supreme Court.

Disclaimer: The views or opinions expressed are solely of the author.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to stay up to date on our product, events featured blog, special offer and all of the exciting things that take place here at Legitquest.

Add a Comment