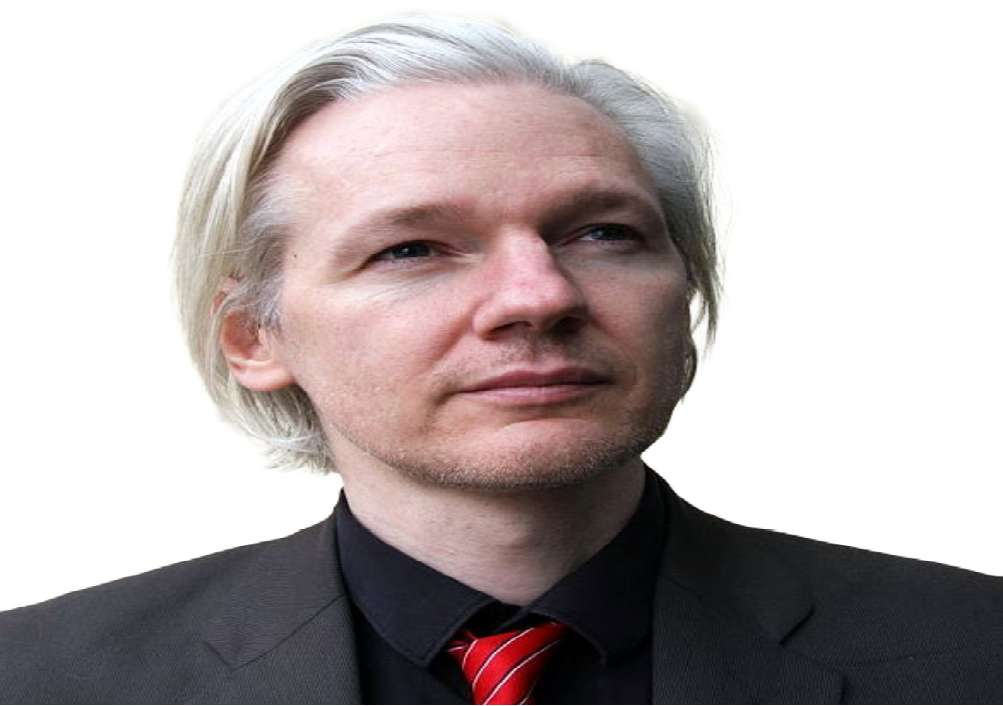

U.K. Judge blocks Julian Assange’s extradition to U.S. citing mental health

London, January 4 (NYT): A British judge ruled on Monday that the WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange cannot be extradited to the United States to face trial on charges of violating the Espionage Act, saying he would be at extreme risk of suicide.

The decision in the high-profile case grants Mr. Assange a major victory against the U.S. authorities who charged him over his role in obtaining and publishing secret military and diplomatic documents related to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, The New York Times reported.

Rights groups and advocates applauded the ruling, but many expressed concern about its rationale. The judge focused on Mr. Assange’s mental health issues, but rejected the defense argument that the charges were an attack on press freedom and were politically motivated.

Mr. Assange, 49, who was present at Monday’s hearing and wearing a face mask, was indicted in 2019 on 17 counts of violating the Espionage Act and conspiring to hack government computers in 2010 and 2011. If found guilty on all counts, he could face a sentence of up to 175 years in prison.

The judge, Vanessa Baraitser of Westminster Magistrates’ Court, said in Monday’s ruling that she was satisfied that the American authorities had brought forth the case “in good faith,” and that Mr. Assange’s actions went beyond simply encouraging a journalist. But she said there was evidence of a risk to Mr. Assange’s health if he were to face trial in the United States, noting that she found “Mr. Assange’s risk of committing suicide, if an extradition order were to be made, to be substantial.”

She ruled that the extradition should be refused because “it would be unjust and oppressive by reason of Mr. Assange’s mental condition,” pointing to conditions he would most likely be held under in the United States.

The ruling on Monday at the Central Criminal Court in London, known as the Old Bailey, was a major turning point in a legal struggle that has lasted nearly a decade. But that battle is likely to drag on, as U.S. prosecutors indicated they would appeal. They have two weeks to do so.

A crowd of supporters outside the court erupted in cheers when the verdict was delivered.

“Today, we are swept away by our joy at the fact that Julian will shortly be with us,” Craig Murray, a former British diplomat and rights activist who has been documenting the hearing, told reporters outside the courthouse. He said that while he was “delighted we have seen some humanity,” the ruling on mental health grounds was an “excuse to deliver justice.”

Rights groups also applauded the denial of the extradition request, but some expressed concerns about the substance of the ruling. Among them was Rebecca Vincent, the director of international campaigns for Reporters Without Borders.

“We disagree with the judge’s assessment that this case is not politically motivated, that it is not about free speech,” Ms. Vincent said. “We continue to believe that Mr. Assange was targeted for his contributions to journalism, and until the underlying issues here are addressed, other journalists, sources and publishers remain at risk.”

Stella Moris, Mr. Assange’s partner, echoed the sentiment, saying that while she was pleased that the extradition request had been rejected, the charges had not been dropped. She called on President Trump to “end this now.”

In a statement, the Justice Department said it was “extremely disappointed” by the decision but “gratified that the United States prevailed on every point of law raised,” and noted that it would still seek to extradite Mr. Assange.

Mr. Assange, who is Australian, rose to prominence in 2010 by publishing documents provided by the former U.S. Army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning. He then took refuge at the Ecuadorean Embassy in London to escape extradition to Sweden, where he faced an inquiry into rape allegations that was later dropped. In the meantime, he kept running WikiLeaks as a self-proclaimed political refugee. He spent seven years there before his arrest by the British police in 2019.

During the extradition hearing, which began in February but was postponed because of the coronavirus pandemic, lawyers representing the United States argued that Mr. Assange had unlawfully obtained secret documents and put lives at risk by revealing the names of people who had provided information to the United States in war zones.

“Reporting or journalism is not an excuse for criminal activities or a license to break ordinary criminal laws,” James Lewis, a lawyer representing the U.S. government, told the court last year.

Mr. Assange’s lawyers framed the prosecution as a politically driven attack on press freedom.

“The greatest risk for him in the U.S. is that he won’t face a fair trial,” said Greg Barns, an Australian lawyer and adviser to Mr. Assange. “Then he could spend the rest of his life in prison, in solitary confinement, treated in a cruel and arbitrary fashion.”

The hearing was stymied by multiple technical glitches and restricted access for observers, which rights groups and legal experts said hurt the court’s credibility and hampered their ability to monitor the proceedings.

Mr. Assange has been held at Belmarsh, a high-security prison in London, since 2019. Mr. Assange remained in custody after the ruling was announced on Monday, but his defense team said they planned to file an application for bail on Wednesday as the appeals process continued.

Many have hailed Mr. Assange as a hero for transparency who helped expose U.S. wrongdoings in Iraq and Afghanistan. But he has also been criticized as a publicity seeker with an erratic personality. The publication by WikiLeaks of emails associated with Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign, which U.S. officials have said were hacked by Russian intelligence to damage her candidacy, also undermined his reputation with many previous supporters.

Mr. Assange jumped bail in 2012 and fled into the Ecuadorean Embassy in London. During his years there, he gave news conferences and hosted a parade of visitors, including the singer Lady Gaga and the actress Pamela Anderson. He had also angered embassy workers by riding his skateboard in the halls.

By the time he was dragged away, Mr. Assange had become an unwelcome guest. Weeks later, he was indicted in the United States.

Mr. Assange’s mental and physical health deteriorated while he was held in prison in Britain, experts warned. Nils Melzer, the United Nations special rapporteur on torture and ill treatment, said in November 2019 that the punishment against Mr. Assange amounted to “psychological torture.”

Doctors said that his health had worsened during the hearing.

News and press freedom organizations, as well as rights groups, have long warned that Mr. Assange’s indictment and a potential trial in the United States would set a dangerous precedent for press freedom.

Prosecutors have never charged a journalist under the Espionage Act, but legal experts have argued that prosecuting a reporter or news organization for doing their job — making valuable information available to the public — would violate the First Amendment. Mr. Assange’s actions remain difficult to distinguish in a legally meaningful way from those of traditional news organizations.

Jameel Jaffer, the executive director at the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, warned that the charges that Mr. Assange still faces “cast a dark shadow” over journalism. The charges focused on pure publication of the material were of particular concern, he said.

“Those counts are an unprecedented attack on press freedom,” he said in a statement, “one calculated to deter journalists and publishers from exercising rights that the First Amendment should be understood to protect.” — NYT

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to stay up to date on our product, events featured blog, special offer and all of the exciting things that take place here at Legitquest.

Add a Comment